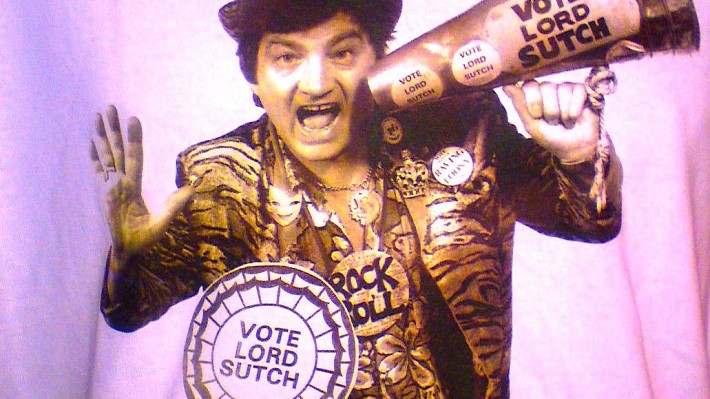

He was the Monster Raving Loony who brightened British by-elections for three decades. But Screaming Lord Sutch was also a shock rock star who frightened the life out of his audiences – and, finally, himself. Investigation by Tony Barrell

THE SUNDAY TIMES (COVER STORY), 2000

David Edward Sutch didn’t die as a politician, as the longest-serving leader of a British political party, the most colourful fringe campaigner ever to wear a rosette. He died as Screaming Lord Sutch, raving monster of rock’n’roll, the man who brought blood, guts and horror to pop music years before Alice Cooper or Ozzy Osbourne or Marilyn Manson. The sight that awaited Sutch’s fiancée, and subsequently the police, on the afternoon of Wednesday, June 16, 1999, was worthy of his own gruesome 1960s stage act.

The scene was a small house in Parkfield Road, South Harrow, the London property he had inherited from his mother, who died 25 months before him. He was hanging by a child’s multicoloured skipping rope from a banister of the staircase. He had always been a prankster, a practical joker, and at first his girlfriend, Yvonne Elwood, thought the 58-year-old leader of the Official Monster Raving Loony party was just fooling around.

The house was a shambles. There was junk and memorabilia strewn everywhere, and the police had to clamber over several metal cabinets. On a bed upstairs, laid out very neatly and deliberately, was what appeared to be his choice of burial wear: a grey Regency stage jacket with a yellow silk flower pinned to the lapel.

None of his friends – and he had a lot of friends – thought he would ever go this far. Some had known for a long time that he suffered bouts of depression, but he had always bounced back, and even the death of his beloved mother was something they thought he would eventually get over. In retrospect, many say the signs were there, that Sutch dropped hints of the suicide he was planning. This cryptic broadcasting of his intentions would have been entirely in character for this strange and complex man – a clown whose public mask of jollity and warmth starts to slip once you begin to investigate the true story of Screaming Lord Sutch.

**************************************************

A few years before Sutch trod the line between pop and politics, he was mining the equally unlikely seam between Jerry Lee Lewis and Bela Lugosi. The dawn of the 1960s was a period of clean-cut crooners and nicely behaved rockers, and Screaming Lord Sutch and his stage act were about as far removed from Cliff Richard and Adam Faith as the death-defying Harry Houdini had been from the sedate conjurers of his time.

He threw live maggots and worms into the audience, which wriggled down décolletages and into beehive hairdos

Early Sutch concerts, in London pubs and coffee bars, would begin with his band, the Savages, racing through the audience to the stage wearing leopardskin leotards. Sutch would start singing while still inside an upright coffin, and would suddenly leap out and terrorise the women in the front row, a long-haired demon with his face painted white and his eyes ringed with black and red. One of his big numbers was ‘Jack the Ripper’, which had him chasing after a shrieking “prostitute” with a long knife, and carrying out a mock disembowelment when he caught her. His props sometimes included fresh pigs’ entrails, and he would throw live maggots and worms into the audience, which would wriggle their way down décolletages and into beehive hairdos. He had girls shrieking and fainting before the Beatles did, and for very different reasons.

Sutch’s repertoire was inspired by a love of spooky films and by boyhood trips to variety shows, the Tower of London, and the Chamber of Horrors at Madame Tussaud’s waxworks. And he didn’t confine his act to the stage: in a moment of supremely bad taste, he made a publicity appearance late at night in the streets of Whitechapel, east London, wearing his Jack the Ripper outfit and visiting the murderer’s favourite haunts. In 1965, summoned to Willesden County Court over a minor hire-purchase matter, he turned up as an archetypal caveman, wearing a leopard skin and sandals and swinging a club.

Publicity was one of Sutch’s favourite words, and the secret of his longevity in the absence of significant record sales. He could so easily have finished up as a pop footnote, a bargain-bin rock’n’roll casualty who enjoyed less chart success than Leapy Lee and Whistling Jack Smith. Researchers might have pointed out that he was backed by some of the greatest rock musicians of the 20th century – guitarists like Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck and Ritchie Blackmore, and the drummer Carlo Little, who later played in a promising new band called the Rolling Stones. But that would have been it, case closed – if Sutch hadn’t, on a wild whim in 1963, turned himself into the most outlandish, original and probably least political British politician of our age.

It was all John Profumo and Christine Keeler’s fault that Sutch entered politics. When this early slice of Conservative sleaze prompted a by-election in Stratford-upon-Avon, the 22-year-old singer paid a deposit of £150 out of his gig earnings to become the National Teenage party candidate, and received 208 votes.

It was a career move that made him a household name, an institution as British as eggs and bacon, Carry On films and the Queen Mother. And three decades later he was still there, a bad penny popping up on by-election platforms up and down the country, losing deposit after deposit but bringing colour to the grey, bureaucratic voting system with his trademark top hat and leopard-print threads, his gap-toothed grin and Official Monster Raving Loony party policies. All work before lunchtime should be abolished, he said, and time should be decimalised (100 minutes to the hour, 10 hours to the day, 10 days in a week) to make life simpler. Traffic police would be made to ride tandems, parliament was to be put on wheels and moved round Britain, and Battersea Power Station turned upside down and used as a snooker table. As he never tired of pointing out, real life was constantly catching up with the OMRLP: people had roared with laughter when he’d suggested lowering the voting age to 18, allowing pubs to open all day, pedestrianising Carnaby Street and decorating the Beatles.

Sutch’s political life had its lean periods, particularly the 1970s, which he called his “wilderness years”. This was when he took his rock’n’roll act to America, and met Thann Rendessy, the blonde model who was to give him his only child, Tristan. But the relationship didn’t last, and they were to be separated by the Atlantic Ocean for most of the remainder of Sutch’s life.

Sutch was almost too successful to be a Loony. He polled more than the SDP at Bootle in 1990

In the 1990s, Sutch was almost too successful to be a Loony. He polled more than David Owen’s breakaway SDP at Bootle in 1990, and hit a peak of 1,114 votes at Rotherham in 1994. Paradoxically, it was also one of his toughest periods. The government had increased election deposits to £500, and Sutch was now in his fifties but had to work harder than ever – gigging and making personal appearances – to feed his political habit. An unwise house purchase in 1992, followed by the collapse of the property market, left him owing around £194,000 to Barclays Bank and facing possible bankruptcy.

On one hand, he loved the electoral shenanigans and needed them for the publicity he adored. On the other, there were signs that he felt trapped, that the Lord Sutch role had become a Frankenstein’s monster. “Sutchy used to say to all of us, ‘I can’t believe how big this has got, I can’t believe it,’” says Rockin’ Dave Robbo, the OMRLP’s minister of performing arts. “I believe he had to live this other person, Screaming Lord Sutch, for all those years, and his own person, David Sutch, dried up.”

Sutch even harboured irrational fears that a freak vote would land him in parliament, where he would have to play the political role for real. The ultimate nightmare, though patently absurd, was that the OMRLP might win outright. As Robbo recalls, “He used to say, ‘What am I going to do if they ever vote me in as prime minister?’”

The message at party headquarters – a large, shabby pub called the Golden Lion in Ashburton, on the edge of Dartmoor – is basically that Sutch was a great bloke, a diamond geezer, a man in a million who redefined the phrase “the life and soul of the party”. As a rabble of leopard-spotted, tiger-striped, zebra-printed Loonies mill around the bar at the OMRLP 1999 conference (suddenly they’re all looking fashionable), the panegyrics and hagiographies come thick and fast.

“He always loved talking to people and finding out what they were interested in,” says Chris Moore, a 42-year-old computer consultant from Gillingham, Kent, who dresses as a sailor and calls himself “the Admiral”. When Moore met him recently and mentioned that he was a yachtsman, Sutch gave him a ministerial appointment on the spot. “He said, ‘Oh, brilliant, then you’re minister for yachts and floating voters!’ He was so interested in people: if you met him once, the second time you met him it was like you were an old friend.”

“Lord Sutch was nothing like people imagined,” says Alan Hope, the new leader of the party (though he technically shares that honour with his ginger tom, Cat Mandu). “You saw him on stage shouting and screaming, but underneath it all he was very, very quiet, very laid-back. He didn’t drink, he didn’t smoke. He was very anti-drugs. If anybody swore in his company, he’d tell them off.” We are sitting outside the Golden Lion, of which Hope is the landlord. The rotund 57-year-old, dressed in a white suit and stetson, gazes over the pub garden. “He’d be here three or four times a year. He loved it down here. I’ve seen Lord Sutch sat out in my garden here, peeling potatoes for Sunday lunch.”

The new deputy party leader, Boney Moroney, 43, from Huddersfield, was another longtime friend of Sutch. “He used to buy me teapots when he came up to Yorkshire,” she says. “I’ve got about 13 or 14 of them. And he bought me a Teasmade, too. He was into tea in a big way; he drank a lot of it.”

Go a little deeper, though, and you get a more balanced portrait. “Dave was a great bloke, but he couldn’t organise a piss-up in a brewery,” says Baron von Thunderclap, 39-year-old minister for transport, saving the dodo, and decimal time.”He was only a front man, as such. The day-to-day running of the party, he had nothing to do with.” Which is probably just as well, since Sutch’s organisational incompetence was legendary. He once admitted to spending two days campaigning in Richmond, Surrey, only to find that his by-election was in Richmond, North Yorkshire.

“He was very forgetful,” says Hope. “His whole life was chaotic. If anyone was ever late for anything, it was him. We are probably the only political party that has ever held two conferences without the leader even turning up. And now he’s going to miss any more that we have, obviously.” At a recent conference that Sutch did attend, he emerged to meet the press around noon still shaving, his face smothered in foam.

“He didn’t realise how utterly annoying he was,” says 67-year-old Cynthia Payne, from her house in Streatham, south London. The former luncheon-voucher madam met the singer in 1988 when they both stood at a Kensington by-election (she for her Pleasure and Payne party, and he for the Loonies). “I used to go and visit his mother, because I used to feel sorry for the old girl, because she was at her wits’ end with him. When he was at his mother’s, he’d say to her, ‘I’m just going out to get some milk,’ and he’d be gone two weeks! Instead of saying to her, ‘Look, I want to get away from you for a while,’ he’d tell a lie. Because he didn’t like to hurt people’s feelings, he would cause more trouble. And instead of telling a girlfriend, ‘Look, we’re finished,’ he would just disappear and get himself in such a mess.”

Payne recalls that it was just such a “disappearance” that caused him to move in to her house, where he stayed “on and off” for about two years from the late 1980s. “I never charged him rent: I wanted him here because he was great fun,” she says. “Everybody loved him.”

Payne was with Sutch when he bought a house in Hastings – “my Chequers” – while ignoring advice to sell his other home in Wembley. “I tried to stop him. ‘No, I want it,’ he said. ‘It’s a nice big place. When I get older I could put all my stuff in it.’ He had a bridging loan. I said, ‘You must sell this other house; it’s going on for weeks and you’re paying interest on it.’ He wouldn’t listen.”

Impulsive, irrational spending is one of the classic symptoms of manic depression – two telltale words that were mentioned at the inquest into Sutch’s death. More properly known as bipolar disorder, it is a condition characterised by alternate highs and lows, and Sutch’s highs appear to have driven him to make eccentric purchases. This was a man, for example, who didn’t enjoy driving but loved buying cars. First there was a metallic-blue Chevrolet Impala, then a 1959 Cadillac. Then came the 1955 long-wheelbase Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith he acquired from an undertaker, which ended up with Union Jack paintwork and, naturally, leopardskin seat covers. Later, during his Streatham period, came the old green Morris Traveller that he saw in a forecourt and couldn’t resist. “He just liked the look of it, so he bought this thing,” recalls Gloria Walker, who worked as an election agent for both Sutch and Payne. “And he hardly used it. I don’t think he drove it more than once or twice.”

There were countless lesser splurges. “He couldn’t pass a market or a second-hand shop without going in,” says Walker, “and he’d usually come out with something, little trinkets he didn’t really want.”

Pat Hellier, 52, who with her husband, Ken, was a part-time driver and assistant to Sutch for 13 years, was often on the receiving end of the trinkets. “We went through a parrot stage. I’ve got several wooden parrots that he bought for me, and parrot earrings. If it was a dress, it was always the right size; if it was a pair of earrings, it was always the colour that I liked. I’ve since discovered that one of the charity shops in Harrow used to put all these weird and wacky things away for him, and he’d just turn up and collect them.”

“He came down to Gillingham a few weeks before he died,” said the Admiral, “and he brought me some soft toys – a dolphin and a penguin. He’d seen these vaguely nautical things and obviously thought of me.”

Sutch was a hoarder, reluctant to throw even trivial things away, and much of the junk he didn’t give to friends ended up cluttering his mother’s house. “She used to cry sometimes,” remembers Payne, “because she was so embarrassed when people came into her house.”

Another bipolar symptom is insomnia, and tales of Sutch staying up all night, talking to friends and fans and drinking endless tea, are legion. “He’d sit up late at night, making cups of tea at 2 and 3 in the morning,” says Walker. “He’d watch late-night shows on TV, like Jerry Springer, and films and horror videos. At his house in Wembley there were a lot of videos, some of them really nasty horror ones. If you’re going to sit up into the night watching things like that, I think those things lurk in the corners of your mind; it’s all right if you’re feeling well, but when you’re depressed they’re likely to come up to the surface.”

If he did get to sleep, often it wouldn’t be until 4am or later, and he might surface the following afternoon. “He always looked as if he had a hangover,” says Hellier. “People used to say to me, ‘Has he been drinking today?’ But it wasn’t that: the whole time I knew him, I’d seen him drink one half of lager.”

Valerie Bird, a former girlfriend, witnessed some of his darker moments. “About 12 years ago, he said he was a bit down. I said, ‘What’s the problem?’ And he said, ‘I can’t face doing this election.’ And I said, ‘Come on, now, that won’t do. This is what you’re known for. Come on, you can do it for me.’ And he went and did it, and he said later that he thought of me all the way through it.”

“The last time I met his mother,” says Payne, “I said, ‘I’m not being rude, but is he all there, Mrs Sutch?’ And she went quiet. She said, ‘Well, he has been in depression clinics two or three times.’ I never took it too seriously, though, because I never thought depression would lead to suicide.”

When you’re top Raving Loony, how can you ever talk to people about a worsening mental illness?

“I was on the Esther Rantzen show with Dave Sutch last year,” says his old drummer, Carlo Little, “and he gave me a videotape of the show. But on the same tape were two BBC documentaries about depression. I finally played them after he died, and there were case histories of different people, and every one that talked wanted to kill themselves.”

There is a tragic irony staring at us in the face here: when you’re top Raving Loony (party slogan: “Vote for insanity – you know it makes sense”), how can you ever talk to people about a worsening mental illness? Sutch’s OMRLP colleagues remember a man full of quick-fire repartee, a natural comedian who could talk the hind leg off a donkey but would never discuss his depressive episodes. “I met him at a May ball in Sutton Coldfield in 1992,” says the party’s “chief encourager”, Tessa Lowe. “I told him that I’d like to stand for election one day, but I had to admit I’d suffered from manic depression. He told me it didn’t matter, because it was the official policy of the party to have Spike Milligan for king. He didn’t once mention his own depression.”

“I spent loads of time with him, driving the party bus, and he would never talk about himself at all,” says Baron von Thunderclap. “But he’d talk forever about his mum.”

Annie Emily Sutch named her son David after one of her favourite novels, David Copperfield. She raised him alone in north London after her husband, William, died during the second world war: he rode a motorcycle straight into an air-raid shelter in a blackout, when Sutch Jr was less than a year old. He adored his mother, and when she fell and broke her hip in 1997, aged 80, he decided to abandon his plans to stand against Tony Blair at Sedgefield in the approaching general election. “Ever since she fell, I have had my mind on her and can’t concentrate on politics,” he said. “I’ve got to visit her every day in hospital.”

Weeks later, Annie Sutch passed away. “She died on the eve of the election,” says Payne, “and Sutch said to me, ‘I’m so glad I didn’t do the election.’” He gave her a full Loony funeral, attended by party members wearing their best wacky outfits, at St Paul’s in South Harrow – the church that would be the venue for his own funeral two years later. And at some point during those two years, he stipulated exactly the kind of sendoff he wanted.

**************************************************

Early in 1999, having lost touch with Sutch for a while, Cynthia Payne answered the telephone to one of his rock’n’roll associates, asking if she would attend a Screaming Lord Sutch gig at a pub in Hammersmith, west London, on April Fools’ Day. “Sutch would always get other people to ring up,” she says. “He knew that I knew he was using me for publicity.” She went along, and immediately noticed that Sutch was behaving oddly – even for him. “All of a sudden, I saw him peering round a door, with a big smile on his face. He didn’t think I’d seen him. Then he darted back behind the door.” Later, during his act, “he came off the platform and gave me a quick kiss on the cheek. It was weird; it was as much as to say, ‘Thanks for coming’ or Goodbye.’”

Before she left the pub that evening, Payne casually invited Sutch to come and visit her sometime soon. “He looked at me with a very sarcastic smile, as much as to say, ‘You’re not going to see me any more.’”

On Thursday, May 13. Sutch spoke to The Times, reacting to the news that candidates’ deposits for the European elections in June had been raised to £5,000. “It’s a bad day for the Loonies,” he said. “I had got people all over the country who were going to stand, but this is now the first time we’re not going to contest the Euros… It is a sad day for democracy.”

Two days later, he turned up at Rockin’ Dave Robbo’s 50th-birthday party in Gillingham. “It was the last time I saw Sutchy,” says Robbo. “I’d had two messages on the phone saying, ‘I’m late, Robbo, I’m late, but I will be there, I will be there, I promise you I will be there.’ He came in with carrier bags of presents, leopardskin slippers, toys for the kids, and signed a lot of autographs. But he didn’t look his normal self: he looked a bit down.” There is a very likely explanation for this: Sutch was a great animal-lover, and his old Yorkshire terrier, Rosie, had died that day. “It’s only been two years since Mum died,” he told another friend. “Now Rosie. What next?”

Nevertheless, around this time, he was still announcing positive, international plans for the future. He told a broadcaster at Radio Napa in Cyprus that he wanted to set up an OMRLP branch on the island. He spoke on the telephone to his old friend in New Jersey, Ron Kellerman, the 55-year-old musician he had stayed with during trips to the US. “I’d had some health problems with my heart, I was really depressed, and I told him about it,” says Kellerman. “And he said, ‘Ronnie, what you’ve got to do is get yourself all healthy, ’cause I’m coming to America and I’m going to do a show in Vegas on Hallowe’en – the whole stage act, with the coffin.’ He was cheering me up.”

It was in Las Vegas that Sutch planned to marry Yvonne Elwood, a 41-year-old teacher. The couple were dividing their time between his mother’s old house in Harrow and Yvonne’s home in Reading, and at the inquest she said he had not seemed to be unhappy during his last days. Even his financial problems seemed to be a thing of the past. “He was just beginning to turn the corner,” says Payne. “He had got out of his debt.”

Soon after Robbo’s party, Sutch telephoned him. “He said, ‘Dave, Yvonne’s just gone back to Reading. I’ve dug the hole in my garden and I’m burying Rosie. And I needed to talk to somebody.’ And the very last words I said to him were, ‘I love you to death; you’re like a dad to me.’ He was so chuffed, and he put the phone down.”

Sutch attended the Rolling Stones convention at the Brixton Academy on Thursday, June 10, and received a warm reception when he belted out one of his signature numbers, Chuck Berry’s ‘Roll over Beethoven’, on stage that night. Backing him were the Carlo Little All Stars. But his voice wasn’t on form. “He only did one number, because he wasn’t feeling well – he had a cold or flu type of thing,” says Little. “So he said, ‘Just put me down for one.’ But when he got on stage, he wanted to do another one. But there wasn’t time: the Academy said if we ran over, there’d be a fine.”

On Sunday, June 13, Sutch went to a concert at the Beck Theatre in Hayes. It was a 1960s night, with acts like the Tornados, Jess Conrad and Susan Maughan on the bill. But Sutch didn’t perform; for most of the evening he remained in a seat on the side of the stage. “I knew straight away he wasn’t his normal self,” says his old friend Ron Long, who saw him. “He looked very ordinary. He was dressed very shabbily.”

Two nights later, the world’s greatest comedy politician hanged himself. The last diary entry scribbled on a nearby calendar read: “Depression, depression, depression is too much.” In a notebook, he had drawn a cartoon of himself in his OMRLP getup, circled it and written the words “Loony victim”.

Loonies, bikers, punks and pop stars joined Sutch’s family and friends at his funeral on Monday, June 28. ‘Roll over Beethoven’ blared inside the church, and there were bouquets in the shape of top hats and teapots; Sutch was buried next to his mother, and there was a rock’n’roll wake at a hall in Wembley. “If he was alive, he would have enjoyed it,” says Baron von Thunderclap.

I want to go with a lot of style. I want a mahogany coffin with solid gold brass handles

New evidence, however, reveals it wasn’t exactly what he had in mind. After the funeral, amid the skipfuls of junk in the house, a note was found in Sutch’s unmistakable spidery handwriting on a scrap of thin card. It may be the closest thing to a will he ever wrote.

“No money down here,” it begins, mysteriously, and continues: “Now when I go over the other side I want to go with a lot of style. I want a mahogany coffin with solid gold brass handles with a polish on the nameplates on top. I want a red velvet with a layer of lead. I don’t want it to rot. I’m going to have the best funeral this town has ever seen. I want a black coach and horses with mauve curtains on the back.” The note then ends with a typical piece of Sutch absurdity – a request that his body be equipped with two of his favourite engines of publicity. “I want a TV and a phone. I want to call my bank manager and my solicitor to make my will.” ♦

Tony Barrell’s acclaimed book Beatlemania is available all over the place.

© 2014 Tony Barrell

Pingback: The Third Lord Of Harrow: Screaming Lord Sutch at Let It Rock « Paul Gorman is…

Back in 1969, my brother bought a copy of “With Heavy Friends” because of who those friends were. I was only 11years old and even I knew it was dreadful, but I thought the cover with the Union Jack Rolls Royce and the way he was dressed was very cool. And that’s all I knew about him until I read your article. He appears to have had a great sense of humour, which is something I greatly appreciate.

I stand corrected as to when my brother bought that record; it must’ve been 1970 or 1971.

What happened to the Union Jack car?

I don’t know. Do you?