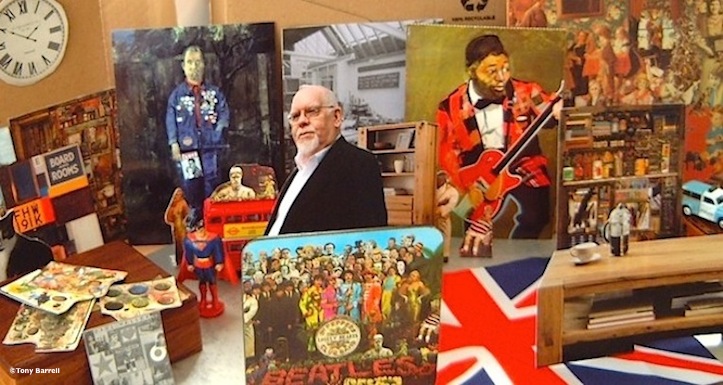

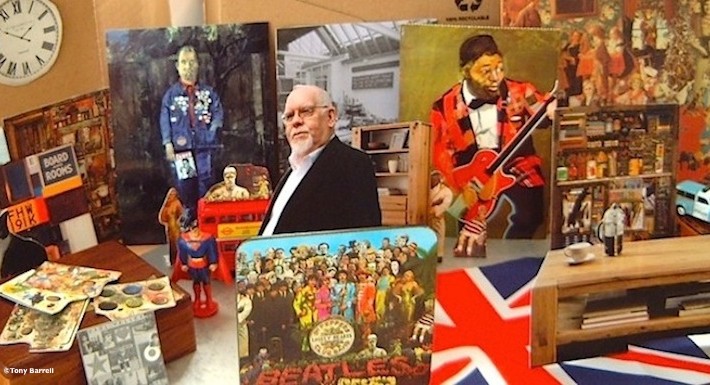

Sir Peter Blake’s studio is a pop-art treasure trove. Tony Barrell goes exploring

THE SUNDAY TIMES, 2012

If Sir Peter Blake wasn’t our greatest living pop artist – if he was something more ordinary, like a bus driver or milkman – the programme-makers would be straight round to his west London studio to film an edition of The Hoarder Next Door, The Man Who Couldn’t Move for Mountains of Rubbish, or one of those other “trash porn” shows that clutter the TV schedules. As Blake leads me on a winding path through his art studio, a bearded old man in a black suit resembling Father Christmas in civilian disguise, it quickly becomes clear that this sprawling place is a repository for his lifelong collection of…. well, stuff. If you’re ever short of dolls, toy elephants, model ships and miniature superheroes, this is the place to come. Blake has probably been to more junk shops and garage sales than his friend and contemporary David Hockney has been to tobacconists.

Some of the things in his studio are familiar. The waxwork of Sonny Liston and the figurine of Snow White both appeared on the Sgt Pepper cover

Blake is a graphic designer, a printmaker and a highly valued painter – one of his paintings, Loelia, World’s Most Tattooed Lady, changed hands in 2010 for over £330,000 – but he is perhaps best known as a collagist, and his collages can be three-dimensional. In 1959 he took an old freestanding cupboard, stuck some glamorous pictures of Brigitte Bardot, Marilyn Monroe and Kim Novak on it, and called it Locker. Any of these objects in his studio could, at any time, become part of a work of art. Some of them are immediately familiar because they have already done that – look, there’s that waxwork of the boxer Sonny Liston and that charming figurine of Snow White, both of which appeared on the sleeve of Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

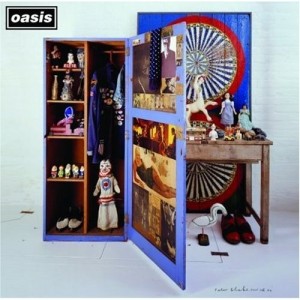

Pop stars who need an unforgettable cover for their new CD ought to come straight here and see what they can find. That’s exactly what Noel Gallagher did several years ago, when he wanted some artwork for the Oasis compilation album Stop the Clocks. “Eh-up, big feller, we’ll ’ave that locker with the girlie snaps on it, that Snow White, and that bloody great dartboard,” is probably more or less what the Mancunian minstrel said, and another classic 3-D collage (pictured below) was born.

On June 25, 2012, Blake hit the age of 80, prompting a cluster of celebratory events. He recently unveiled a new Pepperish collage featuring himself, his wife Chrissy, his children, and a host of famous friends and influential Britons. He had summer exhibitions at the Royal Albert Hall, the Mall Galleries and the Fine Art Society in London, and Blake’s own mobile art gallery – a converted double-decker bus with his pop-art designs all over it – was whizzing around and welcoming visitors. As if that wasn’t enough, the exhibition Peter Blake and Pop Music started at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester just before his birthday. There has been so much Blake business going on this year that even the artist doesn’t have a handle on it all. When I mention in passing that I’d just seen an exhibition of his prints at a gallery in Godalming, he looks puzzled. “What’s this show in Godalming?”he asks. It was called Sir Peter Blake – A Solo Exhibition. “I don’t know about that. They put shows on now and I don’t always know they’re on.”

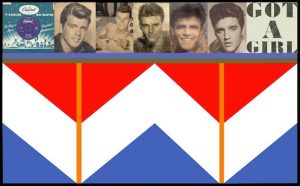

I did a painting called Elvis and Cliff, which I suppose was about the relationship of American rock’n’roll and English rock’n’roll. I’m slightly ashamed of that one now

The Chichester exhibition looked the most unmissable, documenting the extent to which Blake broke down the barriers between fine art and popular music. Blake is important because he did that from both sides: long before he brought art into pop with a series of famous album covers, he brought pop into art by using rock’n’rollers like Elvis Presley and Bo Diddley as subjects for paintings. As early as 1961, he completed a ground-breaking multimedia work, named Got a Girl after a 1960 single by the Four Preps, an American vocal group. The song is about a boy who is desperate to snog his gorgeous girlfriend, but when he tries it he finds that she is really in love with a long list of pop stars, including Fabian and Ricky Nelson. Blake’s painting (pictured) not only features all the singers mentioned, but also has the actual 45rpm record stuck on it. “The idea,” explains Blake, “was that you took the record out of its envelope on the picture, played it, and while you listened to it you looked along the line of pop stars that related to the lyric. The record was stolen once and we couldn’t get a replacement, so we just put any old record in there. But somebody eventually gave me another copy. But it’s fixed in now, so you can’t take it out any more.” Not all of his early works were this ingenious. “I did one called Elvis and Cliff, which I suppose was about the relationship of American rock’n’roll and English rock’n’roll. I’m slightly ashamed of that one now.”

As with radio, spaghetti and toilet paper, the invention of pop art can’t be credited to one person, but to a group of like-minded thinkers, of which Blake was one. He recalls the art critic Lawrence Alloway throwing a dinner party in the 1950s. “There were mainly abstract painters there, we were talking about art, and I was trying to explain that I was attempting to make art that communicated to young people in the same way that pop music did. And Lawrence said, ‘What, a kind of… pop art?’” Blake says he failed to reach the teenyboppers and bobbysoxers at the time, but he was thrilled when he went to this year’s Brit Awards. He had designed the actual 2012 award, a red, white and blue pop-art statuette, and the singers Adele and Rihanna publicly enthused about winning a genuine “Peter Blake”. “Suddenly, what I had attempted to do all those years ago, to communicate absolutely naturally with this audience of music people, it finally happened.” He wasn’t a household name for everyone at the Brits, though: one person was overheard asking who Blake was and being told he was “that bloke with the beard who looks like Gandalf”.

Blake’s poppiest work has its roots in a genuine passion for music. In his teens he was a jazz fan, visiting swing and bebop haunts like the Dartford Rhythm Club, and the Flamingo and the 51 Club in London. A Rat Pack enthusiast in the 1950s, he did a few paintings featuring Sammy Davis Jr, and when the performer came to London, Blake took one to his hotel as a gift. “I think it was the May Fair Hotel. The doorman took the painting, in an old carrier bag, and I had a feeling Sammy Davis never received it. Years later, I became friendly with Tony Curtis when he was still friendly with Sammy, and I asked him to check whether he got it, but I never found out.”

On February 17, 1963, Blake met the Beatles for the first time, when they were in Teddington to film a TV show

Blake’s life has been rich with pop memories. Born into a working-class family in Dartford, Kent, he lived “50 yards away” from Mick Jagger. In the early 1960s, Blake taught at Walthamstow school of art in east London, where the young Ian Dury was one of the students. Blake says that he and Dury ended up becoming mutual heroes, particularly when the Essex lad became a successful singer. Blake remembers how standing up was a constant problem for Dury, whose left side had been withered by polio. “At Walthamstow you’d always see him falling over .”

On Sunday, February 17, 1963, at the age of 30, Blake met the Beatles for the first time, when they were in Teddington to film the pop show Thank Your Lucky Stars. “A friend of mine was the set designer for the show, and he said, ‘Come and watch the rehearsals,’ and I ended up staying for the show as well, though I was ostensibly too old for it.” He thinks that it was during this encounter that John Lennon wounded him with an offhand remark. Blake mentioned that in 1961 he had won a big Liverpool art award, the junior John Moores prize, with his painting Self-Portrait with Badges. Lennon was aware that his dear friend Stuart Sutcliffe, the Beatles’ former bassist, had also entered a canvas for that award. “And John said to me, ‘Stuart should’ve won that.’”

Blake only received a one-off £200 fee for the cover of the multi-million-selling Sgt Pepper

What ought to be Blake’s greatest pop memory has become a sore subject, though this gentle and patient man is too polite to refuse to talk about it. When Robert Fraser, his gallery owner in the 1960s, secured him the commission of the Sgt Pepper cover, Fraser (who was “out of his mind, stoned the whole time”) carelessly subcontracted the job to Blake. The upshot was that the artist only received a one-off £200 fee for an album that has since sold more than 30m copies, not to mention countless T-shirts, fridge magnets and iPhone covers. Even that £200 had to be shared with his first wife and collaborator on the project, Jan Haworth.

Why did they have lifesize cutouts made of all the people on that cover; couldn’t they have saved a lot of time by doing a flat collage? “I wonder, too, why we didn’t…” he says, then thinks some more. “Well, I think the idea was that it was to be a photograph of the Beatles. We weren’t going to be given a photograph of them to work with – they would actually be photographed, so we had four human beings to work around, and then it was logical to make a set.”

Nearly 60 years after he made this work of art, Blake still faces a barrage of requests to sign copies of it – he has come to dread the sight of people lurking with 12-inch-square carrier bags – and people are still trying to unlock its mysteries. “We had a Mail reporter at the house this morning,” he gasps, “which has never happened in my life. He was asking about a photograph.” The picture shows Paul McCartney’s father, Jim, and a crowd of people around a bass drum with the words “Jim Mac’s Band” on it, and it has been suggested as the prototype for the Sgt Pepper art. “I guess the reporter wanted to ask me if I’d copied the photograph. But Paul didn’t show it to me until years after Sgt Pepper. Anyway, Chrissy said I wasn’t there, and he left his card.”

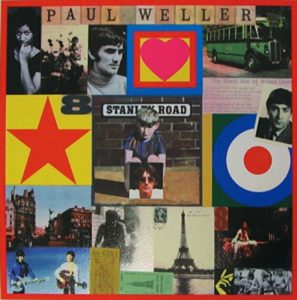

Despite being a financial disaster for him, the Sgt Pepper cover became Blake’s own personal calling card. It was the reason he was asked to create two more classic collages in the 1980s: the cover for the first Band Aid single, and the poster for Live Aid. He reached another high point in the mid-1990s with the sleeve for Paul Weller’s Stanley Road ( pictured). Taking time out from touring and promoting his latest album, Weller reflects on that work. “I was really surprised when I heard Peter was up for designing my sleeve,” he tells me. “I thought he would have been unaware of my work, and almost unapproachable because of his standing in the art world.” The Modfather and the Godfather of Pop Art pooled ideas and images, and the cover became a showcase for Weller’s favourite things. “My choices were the mod on his scooter,” says Weller, “Georgie Best, a very young Aretha, the Small Faces figurines, the old green bus – which reminded me of Surrey County buses from my youth – and the pictures of my mum, dad and sister from the 1950s and ’60s. The sleeve is iconic, isn’t it? It’s a work of art and a statement of its time. I loved it and always will. I love the stark colours and energy it captures. It’s like all great sleeves – it gives you a very clear idea of the music inside.”

Now that he is the darling of the 2012 Brit Awards generation, would Blake like to make art work for the pop stars of today, like Lady Gaga or Coldplay? “I’d take it on its merits – it would depend,” he replies. “I’m not fond of rap music, so I wouldn’t want to go in that direction. And I’m totally against the invented X Factor pop stars. I positively don’t watch that sort of thing.”

A little-known fact is that Blake turns up in the film Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, playing an irascible man in a painting that comes to life

Look at a Blake collage for a second and third time and you’ll often see something you didn’t see before. Research his life and work, and all kinds of surprises turn up. An extremely little-known fact is that Blake himself turns up briefly in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, playing an irascible man in a magical painting that comes to life at Hogwarts (at the request of a friend who worked on the film). So whoever compared him to Gandalf at the Brit Awards wasn’t far wrong. And take the cover he did for his musical hero Brian Wilson’s 2004 album, Gettin’ in Over My Head. In the bottom right-hand corner is a picture of Wilson with a hand on his shoulder, to illustrate the track ‘A Friend Like You’. “I cut out Jonathan Ross’s hand for that,” Blake laughs.

There are still new surprises waiting to emerge from that incredibly cluttered studio. When Paul Weller visited the artist’s previous studio in Chiswick, he noticed a portrait on the floor and asked him about it. “He said it was something he’d started in 1964 and was still working on!” recalls Weller. “I love that artistic viewpoint – that your work is never finished, and that need to look forward. It’s a shame musicians aren’t like that any more.” ♦

© 2014 Tony Barrell

Tony Barrell’s book The Beatles on the Roof is out now in the UK. You can read about it here, and buy it here.

0 comments found

Comments for: BLAKE SUPERIOR