Tony Barrell watches Essex collide with California – as Alisha’s Attic invade Mendocino to record their delightful third album

THE SUNDAY TIMES, 2001

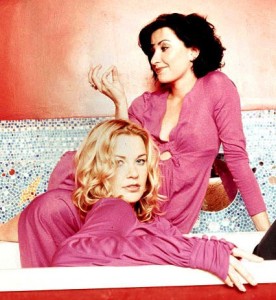

Karen and Shelly Poole, inseparable pop sisters, are skipping down the road to the sea, hand in hand under a vast blue Californian sky. It only takes a bit of imagination to turn the asphalt into yellow brick, and before long they are speculating about the roles they would play in an imaginary remake of The Wizard of Oz, one of their favourite movies and a recurring cultural reference point.

“Karen would be ‘If I only had a brain,’ ” says Shelly, “with straw hanging out of every orifice. Everyone would be like, ‘Yep, if she only had a brain!’ ”

“Shelly would be Toto,” bitches her blonde sister, brightly.

“The little woofer!” laughs Shelly, before she rejects the idea. “No, I’d be Dorothy, darling. Or I’m not playing.” The pair dissolve into glass-breaking giggles, in perfect harmony.

Take two other chirpy, cheeky Essex girls and plonk them here in Mendocino, a curious little town on the West Coast of America, and the result would probably be culture shock and a pair of tickets for the next return flight to Heathrow. But that’s because a random selection of young women from Britain’s most maligned county is unlikely to turn up two free-spirited daughters of a 1960s pop star, with a passion for old Hollywood musicals; two singer-songwriters, collectively known as Alisha’s Attic, reliving an experience that changed their lives. For this is a return visit for 30-year-old Karen and 28-year-old Shelly, a reunion with the friends they made here last year, when the place they call “Mendo” inspired them to make the best record of their career.

In Mendocino, people stop and say hello in streets that look like sets from Murder, She Wrote, which was filmed here

Once a quaint coastal lumber town, for several decades Mendocino has been a refuge for America’s alternative set: musicians, painters, sculptors, craftspeople, touchy-feely healers, health-food dealers and plain, ordinary hippies. It’s a suitably wild and unspoilt site for back-to-the-land types to build their own log cabins, dig their own wells and generate their own power with windmills and solar panels. It’s cut off from the rest of the world by hills covered with forests and vineyards – plus the odd patch of wacky baccy – and by the average motorist’s terror of winding, vertiginous roads. In town, people stop and say hello to you in streets that look like sets from The Truman Show or from the TV series Murder, She Wrote – which was actually filmed here.

To Alisha’s Attic, it’s heaven, fantasy made reality, a place of “smoky-dopey, loopy-doopy, twirly-whirly” people. But Karen and Shelly didn’t come here to join a commune, or even to marvel at the tall redwood forests tumbling down to the Pacific, where seals bob up and down in the surf around rugged bluffs. They came here to meet a certain studio wizard, at a critical point in their careers, in the hope that he could help them turn their fortunes around.

Things had begun so well for them. Their 1996 self-written debut album, Alisha Rules the World, went double platinum. Produced by sometime Eurythmic Dave Stewart, it generated four hit singles – including ‘I Am, I Feel’, later nominated for an Ivor Novello award – and four-star reviews praising it for its “sassy, catchy songs” and “warm, caressing harmonies”. With their trippy thrift-store fashion sense, colourful make-up and wild hair, Alisha’s Attic became the toast of television music shows and teen-magazine lifestyle questionnaires. The press seized on their Essex roots and pop pedigree – their father is Brian Poole, who had a No 1 in 1963 after his band, the Tremeloes, were signed by Decca on the very day the label turned down the Beatles.

Maybe there was too much pressure on Karen and Shelly to repeat the success of their first album, prove it wasn’t a fluke; maybe they weren’t quite ready to go back into the studio. But in 1998 they went to New York and worked with the producer Mark Plati. The second album, Illumina, was lukewarmly received and sold a disappointing 100,000 copies; the last single taken from it, ‘Barbarella’, didn’t even make the Radio 1 playlist. Rumours spread that the band were about to be dropped from their label, Mercury Records, and the sisters went to their old friend Dave Stewart’s place to sulk and be consoled. Fortunately, Mercury’s managing director, Howard Berman, was supportive too.

“We were in the record company by the skin of our teeth, and we totally knew that,” remembers Shelly. “We nearly did get dropped, I’m sure, even though Howard was like, ‘We still believe in you; you’ve got as much time as you want for the next album. Just come up with something good.’ No pressure!”

The attic in Barking is their magic room: their spiritual retreat, their Narnia wardrobe

They were exceptionally lucky: in the fickle world of pop, few artists get a last chance. It was time for the sisters to retire to the Barking attic of their friend Terry Martin, Karen’s ex-boyfriend and a co-writer since the start of their career. This is their magic room – their spiritual retreat, their Narnia wardrobe – which Terry converted into a studio when they were all teenagers with big dreams of becoming pop stars, and which gave them half of their name. Alisha was a kind of everywoman half-devil, half-angel character that the girls invented, and they connected the name to the unique creative “vibe” that they felt when they wrote songs up there. A kind of sisterly mind-meld happens when they put their pop heads on; they may start with a pile of lyrics from Karen and some chords and melodies from Shelly, but there’s no telling where they will end up.

This time they broke away from the attic – “It was too small after a while” – and decamped to a warehouse in Battersea lent to them by the fashion designer John Richmond, another friend. The songwriting setup was frankly bizarre, and you can see why they needed the extra space. In addition to the sisters and Terry, and Terry’s border collie, there was Karen’s boyfriend, the session guitarist Jimmy Hogarth. “Yeah, Karen enlists them,” says Shelly. “I can never tell anyone what it’s like to be in the studio when we’re writing,” says Karen. “That’s why we write with my ex-boyfriend and my boyfriend – we write with people who really know us, because our dynamic’s so bizarre.”

They were there for four months, working 10-hour days and chilling out to records by Dusty Springfield, the Mamas and the Papas, Donovan, Love, and Simon and Garfunkel. Around the time of the second album, they had lost the enjoyment of composition in the mass of high-tech programming that recording had become for them, but now the muse was returning. “We wanted to find a way of becoming naive again,” says Karen, “because that’s how we started off and that’s where the magic comes from.”

“The joy actually came back to it,” says Shelly, “and it was like, ‘Oh, we’ve written such a great song, it’s a classic.’ ” The new material was “organic”, they say; it was uncluttered, simple, beautiful and free. Far out, man. They didn’t know it then, but they were clearly already on their way to Mendocino.

Casting around for producers, Mercury Records suggested Bill Bottrell. It was an inspired choice; Bottrell, who was the producer and a co-writer on the first Sheryl Crow album and has worked with Madonna and Michael Jackson, makes high-quality pop music using techniques that many of today’s producers would call eccentric, or at least nostalgic. For his basic tracks, he likes to capture the energy and humanity of a band playing live in the studio, rather than laying down a lot of fussy individual recordings of single instruments. He prefers to record vocals in a single take, instead of creating total perfection by “dropping in” bits of singing here and there, and he prefers to use real guitars and drums rather than computer-generated fantasy sounds. But there was no guarantee that Bottrell would accept the commission: he came with a reputation for extreme choosiness, for turning down household names and only signing up to projects that really interested him.

Bottrell, a slim, intense 48-year-old with glasses and the greying goatee of a minor pharaoh, is sitting in his roomy, informal recording studio in Caspar, just outside Mendocino. Just over a year ago, he was here playing a stack of demo CDs he had been sent. When Alisha’s Attic came on, singing a number called ‘Sex Is on Everyone’s Tongue’, his ears pricked up. “l heard a spark, and I knew I should give them a call,” he remembers. “I liked the vocals and the clever lyrics. It was an act that had a centre and a spirit, and I was intrigued.” The original idea, still far from finalised, was that Bottrell might produce just one song for the new album. “And Howard said we had to go all the way to Mendocino to meet Bill Bottrell,” says Karen. “We were like, ‘What, just for a meeting? All that way seems a bit silly. Suppose we don’t hit it off?’ ”

Off they went to meet the wizard, anyway, taking the winding highway north of San Francisco for three hours. By the time they hit Mendo, it was in darkness and deathly quiet, and they weren’t really in the mood to appreciate small-town America. “We were totally jet-lagged,” says Shelly. “We thought, ‘Oh my God, where are we?’ It was actually a bit scary; it was like Twin Peaks.”

“And we thought, ‘What on earth are we doing? We should be doing our album back home, getting on with it. What the flipping heck are we doing in the middle of Nowheresville?’ ” says Karen.

They pitched up at Bottrell’s house, an imposing converted school, and met the producer and his band. “We had a little dinner,” says Bottrell, “and Shelly and Karen sat down like stars at the table – just vivacious, friendly, healthy and beautiful people – and they took immediately to my band and hit it off. I started doing the dishes, and I remember all of them down at the end of the dinner table just laughing and talking.” They were due to return to London the next day, but their flights were cancelled and they went straight into the studio. “We woke up in the morning,” says Karen, “and we had this beautiful view of the sea. It was unbelievable.”

“There were whales in the bay,” says Shelly. “As soon as l woke up and saw it, it was like, ‘Oh, we’ll be doing the album here.’ ” Her prediction was correct: the first song went so well that they tried a second, then a third, and after the results were sent back to London, Mercury gave them the green light to continue.

Shelly nearly cried when she heard that her musical hero Neil Diamond had just bought a house in the tiny town of Yorkville, not far from the studio

Over the next two months, the sisters made themselves perfectly at home. For the recording of their first album, they had erected a mock bedsit in the London studio; to achieve the right atmosphere this time, they created a kind of hippie haven, burning Mexican religious candles and draping the studio with flowers and frippery. It was a makeover reminiscent of what rock bands did in the 1970s, when it was the done thing to “get your bead together in the country” and self-indulge on a huge scale – though Alisha’s Attic stopped short of furnishing the studio with bales of hay, the way the band Yes did for their Tales from Topographic Oceans epic. “We went out into a field and picked loads of daisies, and spent hours putting daisy chains together while the band were setting up,” says Karen, “and just dangled them from our mikes. They went off really quick and we’d have to go out and get more, but we’d always keep the dead ones up as well. We bought lots of sari fabric, too, and draped it all around to make us feel a little more ethnic.”

There was the occasional glass of wine as they worked – sometimes more, as on the night that they got a little too rock’n’roll and were turned away from a restaurant for being rowdy – and they would take breaks to jam silly songs or go ten-pin bowling. They found themselves at crazy campfire parties, singing songs like Johnny Cash’s ‘Ring of Fire’, and on the beach Shelly met a shaman with a long beard, who claimed to have roamed all the way from Somerset, and who encouraged her to throw myrrh on the fire for good luck.

Luck, kismet and coincidence are pet preoccupations for Shelly, who “nearly cried” when she heard that her musical hero Neil Diamond had just bought a house in the tiny town of Yorkville, not far from the studio. “I went to check it out,” she says. “I stopped, pulled over, sniffed the gravel, picked up a couple of stones, checked his postbox. I’ve got pictures of me with the gravel, me with the postbox, me with the house. It was heaven.” Cue much eye-rolling and medallion jokes from Karen, who doesn’t share this particular fixation. “Don’t write any slag-offs about Neil Diamond,” Shelly tells me, “because he’s brilliant, he’s lovely.”

It’s easy to caricature the Pooles as wigged-out space cadets, floating in a dreamy haze from one creative whim to another, following the yellow brick road without a care in the world, but that is to ignore their inner confidence, their determination to do things their way. “If there’s a problem, we will absolutely fight to the death,” says Karen. No sooner had they started recording than they decided they wanted Karen’s boyfriend Jimmy to fly over and join the band on guitar, to preserve some of the character of their demos.

Then there was the row with Bottrell over the song ‘Pretender Got My Heart’, a yearning, latinesque mini-epic that Karen calls “the ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ or ‘Wuthering Heights’ of the album”. The demo version was underplayed and acoustic, but a decision was made to heighten the drama and exaggerate the song’s gypsy feel for the album. When Karen listened to the east-European tinged result, she turned a whiter shade of pale. “I looked at her and she was sheet-white,” says Shelly. Karen – whose boyfriend calls her Regan, as in The Exorcist, when she flies into one of her rages – put her foot down: “I said to Bill, ‘Well, it’s changed from the demo, which was really lovely, into Topol and Fiddler on the Roof, and I’m really worried. So can you please take out all the mandolins, all the zithers, anything that’s making it sound like that, and we’ll start from scratch.’ ”

Like the Pooles themselves, the lyrics on the album swing from upfront feistiness to fairyland whimsy

It’s a testament to Bottrell’s own determination that some of those instruments found their way back, but he hit trouble again when he started overusing the sound of a percussed wineglass. “I became very enamoured of that sound,” he recalls, “and I kept trying to put it on every song. In the end, Karen got very upset and said, ‘You know, we’ve got four wineglasses – I think that’s plenty on this album.’ ” Bottrell and the band were also kept in check whenever the music threatened to become too American, says Karen. “We’d say, ‘Don’t go all Kentucky Fried Chicken, don’t slap my thigh with this one – we’re English.’ ”

It helped that Bottrell had an understanding of the British pop sensibility, having worked with Jeff Lynne, of ELO fame, and the songwriter Thomas Dolby, and being a big fan of Mickie Most, who produced such acts as Donovan, Herman’s Hermits and Hot Chocolate. But the spirit of Mendocino is there in the final mix, too. “Every time you play the record, you can hear the energy we created in the studio,” says Karen, “and that’s not really happened on any of our records before.”

The album, entitled The House We Built and released this summer, sounds like a tasty slab of wholemeal amid the pop pap of our times. As Bottrell says, “These are real people making these songs, doing real things in real rooms.” Not that Alisha’s Attic have suddenly turned into Creedence Clearwater Revival, exactly, or lost any of their appealing flakiness. Like the Pooles themselves, the lyrics on the album swing from upfront feistiness to fairyland whimsy. The song ‘Pilot’, whose chorus is partly an adaptation of the tune to ‘Somewhere over the Rainbow’, belongs in the latter category and is at least the second Alisha’s Attic song to feature a space rocket. “It’s about escape,” explains Karen. “I like the idea of getting out of places by any means: normally it’s flying, supergluing wings on your back or getting in a rocket, or something like that. Not normal means of transport – you can’t get to happy places just by car.”

“You can’t get to heaven on a tractor, as they say,” quips Shelly. Who says that, I ask. “Well, as I say.”

At the feistier end of the scale is the song ‘Can’t Say Sorry’, a blunt refusal to apologise for breaking a lover’s heart. Conversely, the forthcoming single, ‘Push It All Aside’, is an all-you-need-is-love anthem to negotiation and reconciliation, and addresses the bond between the sisters themselves. It’s a subject they have covered before, on their 1997 hit ‘Indestructible’, though the Iyrics can easily be construed as an ordinary, universal girl-boy love song.

Karen would pretend to change into Wonder Woman, taking her hair down and her glasses off as she spun round three times in a blue leotard

Wherever she goes, Karen carries a stack of snapshots of her and Shelly as kids – two cheeky sprites often dressed like twins, grinning against bleak seaside backdrops in Southend or Great Yarmouth. Their childhood sounds idyllic, and not a little old-fashioned. Showbiz was indelibly printed in their genes: their mother, Pam, is a former dancer who used to run their father’s fan club. Growing up in Barking in the 1970s, Karen and Michelle Poole adopted their parents’ taste for musicals and were continually rehearsing their own two-girl shows – Oklahoma!, The Sound of Music, Fame, Grease – and inviting the neighbours over to watch. Shelly learnt to play the piano, guitar, recorder and clarinet, while Karen scribbled poetry, practised ballet moves and pretended to change into Wonder Woman, taking her hair down and her glasses off as she spun round three times in a blue leotard. They would plonk on a Casio keyboard and sing the pop hits of the day, mishearing the chorus of Blondie’s ‘Union City Blue’ as “You, yer. . . you, yer. . . you, yer silly moo.”

The family eventually left Barking for Milton Keynes, but Karen and Shelly felt the lure of London and pop stardom, and each of the girls flew the nest, separately, after leaving school at 16. A council housing department placed them in separate fiats, coincidentally in the same road in Dagenham. These days they live with their respective boyfriends in north London – Shelly has been with Ally McErlaine, the guitarist in the band Texas, for four years – but they are still only minutes apart.

Karen and Shelly’s 29-year relationship has always been a strong and intimate one. “It’s like a good marriage,” says Bill Bottrell. “One fills out the weaknesses of the other one.” But the sisters’ roles within the band that they built are tangled and contradictory. As lead singer, Shelly is the obvious focus, her “honking” (Karen’s word) supported by her sister’s gossamer harmonies. But it is Karen’s lyrics that Shelly is usually called upon to sing, and it is Karen who tends to dominate in interviews and everyday organisation. Shelly tends to be portrayed as the Dolly Daydream one with the paranormal beliefs, the ever-changing hair colour and the obsessive-compulsive tendencies, who can’t go on stage without playing ‘The Sound of Music’ six times on her recorder first, who can’t leave home without kissing the lock and saying: “God keep it safe, and don’t let anybody in.”

But Karen is the one who does yoga, who likes to wear a tiara while reading in bed, and recently spent ages looking for a Wonder Woman costume to buy on the internet. She’s the one with the extensive library of fairy-tale books, amassed while working in a Kensington toy shop. It was Karen who wrote the words about being “a goddess of the moon” and “a sultan of the sun” for ‘Dreaming’, the last song on the album, and it’s Shelly who continually takes the role of her sister’s editor, standing firm and refusing to sing any lines she dislikes. “I packed my lunch box and I forgot to take my keys” was one gem from ‘Dreaming’ that hit the cutting-room floor.

Sometimes they give the impression that they loved their shared childhood so much that they decided to stay in it. As our limo winds its way back to San Francisco for the flight home, I tell them they remind me of Peter Pan and Wendy, playing house in a pop Neverland of their own creation. “Well, you can have your feet on the ground and your head in the clouds,” says Karen. “That’s how I live my life.”

Shelly smiles at her big sister. “You’d have a really long neck, though, eh?” ♦

© 2014 Tony Barrell

0 comments found

Comments for: A TOWN CALLED ALISHA