One of the most sacred buildings in London isn’t a church: it’s a legendary recording studio. Tony Barrell explores Abbey Road

THE SUNDAY TIMES, 2006

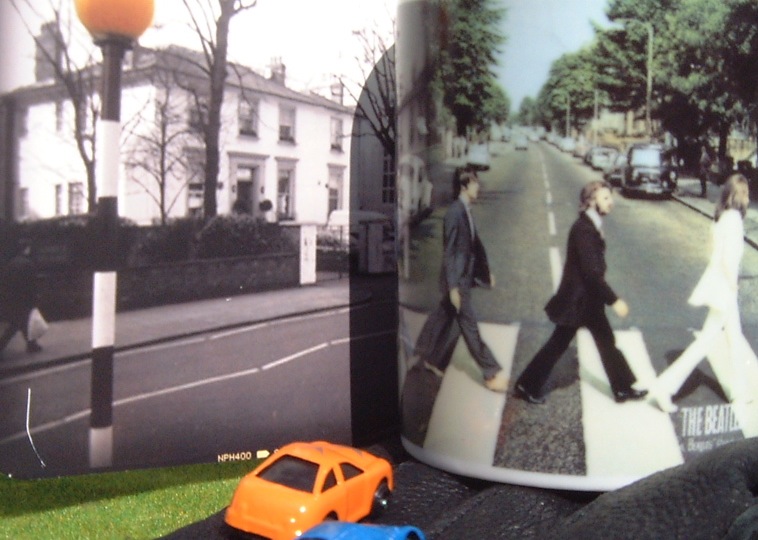

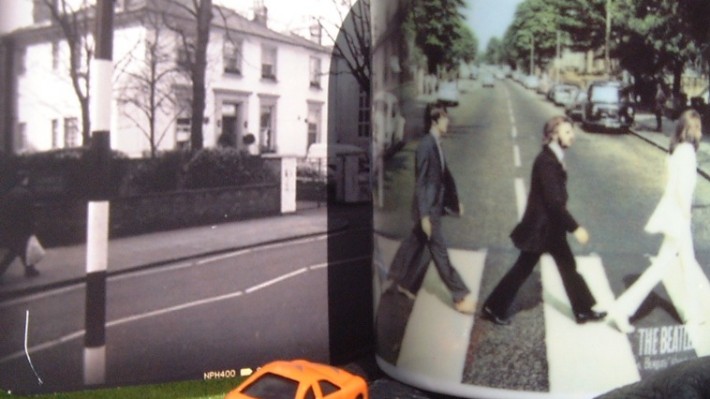

After John Lennon’s death in 1980, hordes of Beatlemaniacs were overcome by a desire to come together, to gather somewhere and share their grief. Many of them streamed into northwest London and poured over the world’s most famous zebra crossing, finally stopping outside a solid-looking, white-fronted Georgian house.

This was EMI’s Abbey Road recording studios in St John’s Wood, the building where the Beatles had created most of their oeuvre, and after which the band named the last album they recorded together. When the bad news broke and the fans descended on the studios, some hi-fi speakers were chosen from Abbey Road’s formidable armoury of equipment and positioned outside, and Lennon’s music was blasted to the masses.

This scene played itself out again almost 21 years later, when George Harrison died from cancer. “They played ‘All Things Must Pass’, and there wasn’t a dry eye in the place,” says David Holley, who, as managing director of EMI Studios Group, is responsible for this hallowed edifice.

But Abbey Road is much more than a shrine to one band. The studio operated successfully for three decades before the Beatles set foot here, and has remained busy in the decades since they split. Pink Floyd recorded The Dark Side of the Moon here; Radiohead used it for their classic album The Bends; Kate Bush has worked here, as have U2, Take That and Coldplay.

Abbey Road quickly became a bastion of British boffindom, a kind of musical Bletchley Park

Number 3 Abbey Road was built in 1830 as a des res with nine bedrooms, a wine cellar and a 250ft garden. It remained a domestic building for almost 100 years, but in 1929, when “zebra crossing” was still just a warning call on African safaris, the Gramophone Company bought it for £16,500 and converted it into a dedicated recording studio. Shortly afterwards, the Gramophone Company merged with Columbia to form Electric & Musical Industries, more snappily known as EMI. The studios’ grand opening, in 1931, saw Edward Elgar conducting his own Falstaff suite.

Abbey Road quickly became a bastion of British boffindom, a kind of musical Bletchley Park. It was here, in the 1930s, that the electrical wizard Alan Blumlein developed binaural sound, better known as stereo. Real music nerds will appreciate the fact that Abbey Road has also given us automatic double tracking (ADT) and direct injection (DI) — plugging an electric instrument straight into the recording equipment, rather than miking it up. Studio two, the room where the Beatles virtually lived in the late 1960s, still has extra-special baffles on the wall for absorbing excess sound — stuffed with dried seaweed, naturally. All recording was done in strict three-hour shifts, clipped instructions issuing from the stiff upper lips of producers and engineers, until the lads from Liverpool came and shook things up. In their later years, the Beatles did heaps of overtime in search of sonic perfection. They slept here, took drugs here and wrote songs here.

I’ve been inside the studios here several times – for interviews, lectures and parties. In 2014 I was photographed inside Studio two, the holy of holies! (See below.)

Progress still marches on at Abbey Road. Today’s digital age has seen it diversifying into cutting-edge audiovisual work. “We’ve got a video services business that chops and edits film, then turns it into whatever format you need — for the web or broadcast or whatever,” says Holley. “And we’ve got a digital product business that creates a whole range of products for the web and for mobile phones.” The boffins still take things apart and scratch their heads here, he says. “They’ve always gone back to the science fundamentals, and they still do. These days, they go into the structure of MP3 files.”

Recording artists are prone to using words such as “warmth” and “magic” to describe the sound here. Is there something spiritual about the place, a je ne sais quoi in addition to all the history and technology? “Well,” says Holley, “there was a fantastic guy who worked here called Alan Brown — if you look right in the middle of the sleeve of the Beatles’ Abbey Road, you can just see the little car he’s driving down the road. And Alan was convinced we’re at the intersection of two ley lines.” Surely Abbey Road’s boffins need to get underground and investigate. ♦

© 2014 Tony Barrell

Tony Barrell’s book The Beatles on the Roof is out now in the UK, USA, Australia and Japan. You can read about it here, and UK residents can buy it here.

0 comments found

Comments for: ABBEY DAYS