He was the greatest escapologist who ever lived. But was Harry Houdini also an international spy? Tony Barrell reports

THE SUNDAY TIMES, 2006

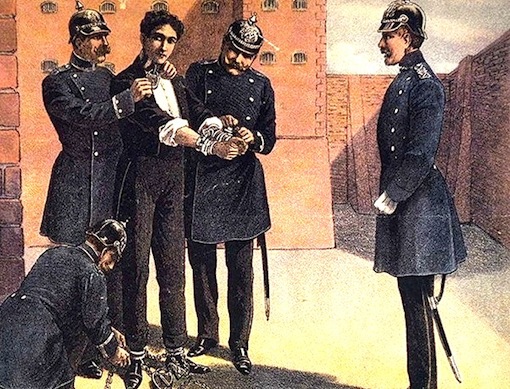

Secrecy was such a fixture of Harry Houdini’s life, it should have been his middle name. We remember him now as the greatest escape artist who ever lived – a tough, squat Hungarian-born Jewish American who freed himself from everything from handcuffs, chains and straitjackets to coffins, iron maidens and torture racks – but he was basically an illusionist; a conjuror. While millions may have swallowed the myth that he achieved his escapes using nothing but brute strength, extreme plasticity and superhuman self-belief, in fact there was often something up his sleeve, so to speak – something he knew about and the audience didn’t.

His equipment would be customised, rigged, interfered with. The myriad containers that imprisoned him would come apart in ingenious ways. To accomplish his famous escape from a big milk can full of water, for instance, he could simply remove the top section, whose ring of false rivets gave a convincing illusion of indestructibility. Even when he leapt shackled into the Mississippi, the Seine or Aberdeen harbour, there was something he wasn’t letting on about the ties that bound him, whether it be dodgy cuffs or concealed lock-picks.

Houdini may have gathered top-secret information when he performed in Germany before the first world war

Enough secrets for one life, you might think. But now there are more nails emerging from the strongbox that has preserved his reputation for 80 years since his death. Two American authors have suddenly announced that Houdini was more than the world’s greatest showman. In their forthcoming biography, The Secret Life of Houdini, William Kalush and Larry Sloman say he was a secret agent; a spy. They suggest that he gathered top-secret information in Germany when he performed there before the first world war. They say he could have been involved in the surveillance of anarchists in Russia. And they maintain that without his services to international espionage, Harry Houdini may not have become the star whose extraordinary exploits are still the stuff of legend today.

By 1894, the year he turned 20, the struggling magician Ehrich Weiss had a wife, a new act and a new name: Harry Houdini. He and his beloved, Bess, joined an American travelling circus and performed as the Houdinis, attracting limited attention with a magic act. But Houdini still needed a lucky break – and it was a Minnesota beer hall in 1899 that apparently served as the escapological equivalent of Liverpool’s Cavern Club in 1961, where one Brian Epstein chanced upon a performance by the Beatles. After Houdini made short work of some cuffs brought to him by the impresario Martin Beck, Beck offered him a headlining vaudeville gig and the princely fee of $60. A full contract was to follow, with Houdini playing smart theatres in big cities from Chicago to Los Angeles, and his fame suddenly began to grow.

According to Houdini’s latest biographers, William Kalush and Larry Sloman, the steep fame curve that the showman enjoyed in the early years of the 20th century wasn’t simply the result of ingenuity, hard work and showbiz karma. They maintain that Houdini formed a secret pact with top American detectives in Chicago, whereby they would help him achieve stardom on the condition that the great escapist teach them the tricks of his trade.

He would turn up at police stations to make dramatic escapes from handcuffs, straitjackets and prison cells

If this extraordinary claim is true, it provides a possible solution to one of the many mini-mysteries within the enigma that was Harry Houdini’s odd career. He would frequently turn up at police stations to demonstrate dramatic escapes from handcuffs, manacles, straitjackets and prison cells – all in the name of free publicity. “I defy the police departments of the world to hold me,” he would boast. At best, this behaviour was wasting police time; at worst, as he casually chucked off the shackles designed to restrain the most psychopathic criminals, he was advertising the inadequacy of police equipment. But, of course, they would have to grin and bear it if they had been instructed to indulge every whim of a covert police adviser. If a performer such as David Blaine were to ask for this level of police co-operation nowadays, would he receive it?

But Houdini’s new biographers go further. They say that Houdini was probably employed by the intelligence services – on both sides of the Atlantic. When Houdini sailed to Britain in 1900, at the midpoint of his life, he met the Special Branch superintendent William Melville at Scotland Yard, escaped from some regulation cuffs and passed on some lock-picking secrets. Shortly afterwards, they claim, Melville became head of the Britain’s secret service and recruited Houdini for espionage work.

It was in the same year that Houdini pitched up in Germany, where he captivated theatre audiences in Dresden and Berlin. This was a time when diplomatic tensions were building: both Britain and America saw Germany as a growing threat to the world order. There were real fears in the US that the Germans were scheming to invade American waters and seize colonies in Latin America. And not only was the German ruler, Kaiser Wilhelm II, pushing ahead with a plan to increase the power of the German navy, challenging Britannia’s maritime supremacy, but he had supported the Boers fighting the British in South Africa.

Houdini was allowed to visit a German munitions factory

One known spy who definitely was operational in Europe around this time – and these were the days before the existence of the CIA, MI5 and MI6 – was Sidney Reilly, on whom Ian Fleming modelled the character of James Bond. Reilly posed as a German in the Netherlands to uncover the truth about Dutch aid to the Boers. He may even have been the same age as Houdini – one of the slippery spy’s possible birth dates is March 24, 1874: the day Ehrich Weiss was born in Hungary.

According to Kalush and Sloman, Houdini may have been snooping into German weaponry secrets. During a three-week run of shows in Essen, in the industrial Ruhr district, he was challenged by the Krupp company to escape from some of its most fiendish handcuffs. Krupp didn’t just make hand restraints: it was a big munitions manufacturer, and Houdini was allowed to visit the factory.

A German newspaper claimed that criminals were lining up to meet the great lock-breaker and learn his secrets. And it was in Germany that Houdini became tangled up in the legal system. He was hypersensitive to criticism, and when a newspaper, the Rheinische Zeitung, claimed he was a fraud who had, among other things, attempted to bribe a policeman into secretly giving him a key to help him escape some fetters at police headquarters in Cologne, he hit the roof. He sued his accuser and, in a highly theatrical turn of events, ended up performing escape routines in the courtroom to clear his name – which he triumphantly did.

Feted by the public, buttonholed by criminals and known to the police, Houdini could hardly have had a higher profile in Germany at this point. If the German authorities got wind of any involvement in espionage, they appear not to have acted on it. In fact, the new biography notes that they were strangely co-operative with him. He was to return to Germany for further shows before the first world war, and he was so popular there that he was rumoured to be a German spy. Houdini later wrote about his involvement in an international exchange of police information: he gave the German police details of top criminals, published in a book by a Boston chief inspector who was a member of the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP), the American-based network founded in 1893 to foster co-operation between cops across the globe. In return, the Germans gave him some similar material from their files to pass on.

Houdini’s next great foreign adventure was in Russia. Arriving in Moscow in 1903, he introduced himself in customary fashion to the police and persuaded them to let him escape from a “carette”, a jail-on-wheels in which prisoners were transported to Siberia. But the Russian police treated him roughly – Houdini later hinted they had even subjected him to an anal examination before the stunt. The writer J C Cannell, in his 1926 book The Secrets of Houdini, claimed that Houdini somehow tore into the metal floor of the vehicle to effect his escape.

Russia and Harry did not seem to get on at all. He found the heavy police presence depressing, complaining of surveillance by “spy detectives”, and was shocked by the laws that meant Jews were barred from entering Moscow’s theatres – it was apparently this kind of east European anti-semitism that had driven his father, a rabbi, to emigrate to the US in the first place. Nonetheless, Kalush and Sloman have another big surprise for us. They claim that the carette escape was Houdini’s passport to the Russian royal family, and that overtures were made to encourage him to become an adviser to the tsar, Nicholas II – a role similar to that filled shortly afterwards by Grigori Rasputin. They also suggest that Houdini was on the lookout for anarchist activity while he was in Russia, and was sending back intelligence reports. Anarchist conspirators were the great international menace of the period – only two years before, the anarchist Leon Czolgosz had assassinated the American president William McKinley.

Various gadgets developed by Houdini in his spare time have a suspiciously strong connection to the world of spying

If Houdini really was this international man of mystery, zipping around the globe and oiling the wheels of history in the run-up to the first world war and the Russian revolution, he would have relished the role. In some ways he behaved like a spy, compulsively revising personal details in a way that made him hard to pin down. “His indifference to dates and facts encompassed virtually all but family anniversaries and house receipts,” wrote Kenneth Silverman in his 1996 book, Houdini!!! The Career of Ehrich Weiss. “Photographs of himself that he dated 1901, for example, can be shown to have been taken in 1908. On various passport applications… he gave his height hit-or-miss as five-four, five-five-and-a-quarter, five-six, or five-seven; his eyes diversely as brown, blue, and gray; his complexion as dark or fair; his year of birth as 1873 or 1874 (for the 1920 census he decided on 1876). Almost no date he supplied in a letter or newspaper article can be trusted.” Kalush and Sloman point to various gadgets developed by Houdini in his spare time that have a suspiciously strong connection to the world of spying, such as a form of invisible ink and steam-resistant envelopes.

In other ways, he was arguably too sensitive and emotional for serious spy work. He worshipped the two main women in his life: his wife, Bess, and his mother, Cecilia. In the notes and billets-doux he sent Bess, or left for her to find around their New York home, he referred to her as “My Dear little Popsy Wopsy” and “Honey-Baby-Pretty-Lamby”. And he was a notorious braggart. He couldn’t achieve any feat, from a new escape to a victory in a legal battle, without advertising and exaggerating it. So if he truly worked as a secret agent, he would have found it a tremendous frustration that he couldn’t trumpet his espionage exploits to the world. But perhaps he did find a way of publicising them and getting away with it: late in his career he became the hero of a series of lightweight adventure movies, the last being Haldane of the Secret Service (1923), a self-produced, self-directed yarn in which “Heath Haldane” thwarts the bad guys using a talent for escapology.

I know that he worked with our soldiers before they went to war, teaching them how to get out of German restraints

Do magicians make good spies? I put the question to John Bravo and Dorothy Dietrich, two magicians who run the Houdini Museum in Scranton, Pennsylvania. “Well, we certainly know a lot of techniques that are not known to the general public,” says Dietrich, who performs Houdiniesque stunts herself, such as escaping from a straitjacket while hanging from a burning rope 150ft off the ground. Both Bravo and Dietrich say the Agent Houdini revelations are news to them. “It’s a possibility,” says Bravo.

“I know he did some experiments with the navy and underwater survival techniques. And I know for certain that he worked with our soldiers before they went to war, teaching them how to get out of German restraints.”

“You know what,” says Dietrich, “the more you study Houdini, the more you learn.”

It’s true: a lot of people don’t know, for example, that in 1910, in his mid-thirties, he became a pioneer of the air, one of the first people ever to fly an aeroplane in Australia. He bought a 60-horsepower Voisin biplane, had some practice runs in Germany, where he was booked for a series of escapology shows, and then set out on the long sea journey. Previous accounts of his brief aerobatic displays Down Under give the impression that he was a courageous and resourceful pilot. What they don’t suggest, and what Kalush and Sloman do, is that this was not just an attempt at making the record books: it was a secret campaign to promote the use of aeroplanes for defence. Harry Houdini was on yet another covert, world-changing mission.

Houdini frequently whinged that escapology was a gruelling business and that he needed to find something else to pay the bills; and he harboured ambitions to leave a more profound legacy, saying he wished that “what brain and gifts I have should benefit humanity in some other way than merely entertaining the people”. If he really did espionage work, that would have gone some way to satisfying those desires. But by the time he had reached his late forties, having amassed a substantial fortune, he had also found a new, very personal crusade.

Houdini visited seances, and used his vast knowledge of stage magic to establish what was really going on when things went bump in the dark

In the wake of the devastating first world war, spiritualism was on the rise. Houdini had an intimate knowledge of the conjuring tricks that “mediums” used to make ghosts of the departed appear to talk, write, throw objects around and even manifest themselves during seances. With the death of his adored mother as a possible catalyst, he decided to expose the shameless fraudsters who were fleecing the gullible and the bereaved. He visited seances, sometimes in disguise, and used his vast knowledge of stage magic to establish what was really going on when things went bump in the dark. He also employed a network of trusted investigators to help him with his medium-busting – and he invoked the language of covert intelligence when he described them as “my own secret-service department”.

One of Houdini’s staunchest opponents was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who, despite having created the super-rational Sherlock Holmes, was an ardent believer. Houdini’s fellow magician Joseph Dunninger later recalled the spiritualists’ reaction: “Resentment was offered everywhere when he would attack these individuals, who would often stand up at their seats in the theatres, and attempt to denounce Houdini.” Spiritualists filed lawsuits against him. “They could not have won the case,” says Dorothy Dietrich, “because how do you get a ghost to come to court? But they figured they could just tie up his money and keep him busy.”

An Indianapolis spiritualist “reverend” taunted that he knew how Houdini did all his tricks, and would reveal all to the public. But there were much worse threats. “I get letters from ardent believers in spiritualism,” he told a Chicago newspaper near the end of his life, “who prophesy I am going to meet a violent death soon as a fitting punishment for my nefarious work.”

“He was getting a lot of threats on his life at the end,” says Dietrich. “In fact, several of his letters that I’ve seen in collections, from the last year of his life, say things like, ‘This may be the last you hear from me – the threats are getting stronger.’”

Houdini didn’t drown hanging upside down in his famous “water torture cell”, as the 1953 Hollywood biopic starring Tony Curtis has it. The apparent truth is that he developed appendicitis but went ahead with a North American tour, and on October 22, 1926, in a dressing room in Montreal, a student from McGill University asked if he could punch him in the abdomen to test his strength. Three days later, Houdini was hospitalised, in agony. He died of peritonitis – his ruptured appendix having led to a severe internal infection – on Hallowe’en. He was just 52.

Kalush and Sloman point to the spiritualists’ crusade against the escapologist and suggest he was murdered. “I have a feeling that that student could have been a believer in spiritualism who wanted to punish Houdini, teach him a lesson, and maybe even do him in,” agrees Dietrich. “In 1926, Houdini went to Washington and asked to have laws passed against the spiritualists, and he did not win the case, because they decided they would claim to be a religion. That was the year he died – so he did not get a chance to go back and prove that they were not really a religion.”

Because he was an escapologist and an enigma, writers seem compelled to unpick more secrets with each new biography

Because he was both an escapologist and an enigma, writers seem compelled to unpick more secrets with each new biography they write. In 1993, in her powerfully analytical work The Life and Many Deaths of Harry Houdini, the British writer Ruth Brandon suggested he was impotent, to explain why there was no patter of tiny Houdinis in the marital home (Kalush and Sloman disagree, saying it was Bess who was unable to have children). Three years later, Kenneth Silverman revealed Houdini hadn’t been as chaste as his sickly notes to Bess imply: he had had an affair with Charmian London, widow of Jack London, the novelist he had befriended in 1915; in her diaries, Charmian dubbed him her “Magic Man” and “Magic Lover”. And now Kalush and Sloman appear to have raked through every known Houdini archive to produce the most comprehensive and controversial biography ever written about the man, with its contention that he was a spy who may have been murdered by a cult.

What next for the Houdini revisionism industry? Is it really so unrealistic to predict an obscenely popular novel, The Houdini Code, alleging that the great man is tenuously connected in tantalising ways to the world’s greatest mysteries, from Lord Lucan to the tooth fairy?

Houdini promised his wife that if he died before her, he would try to contact her from “the other side”. The theory was that if anyone could free himself from the bonds of death, he could. As far as we know, Bess never heard from him. But that doesn’t stop the biographies and the theories from multiplying, a whole century after his heyday. While he may not have found an afterlife beyond the veil, we may never be able to escape from Harry Houdini here on Earth. ♦

© 2014 Tony Barrell

0 comments found

Comments for: AND FOR MY LAST TRICK…