In October 1973, Genesis played to ecstatic fans at the Brighton Dome – and ended Tony Barrell’s rock-concert virginity

SEPTEMBER 2023

As an English schoolboy in 1973, I was fascinated by rock music. I bought up to four music papers a week – New Musical Express, Melody Maker, Sounds and Disc – and read them voraciously. I was especially fascinated by the concert reviews, because I had never been to a professional rock concert.

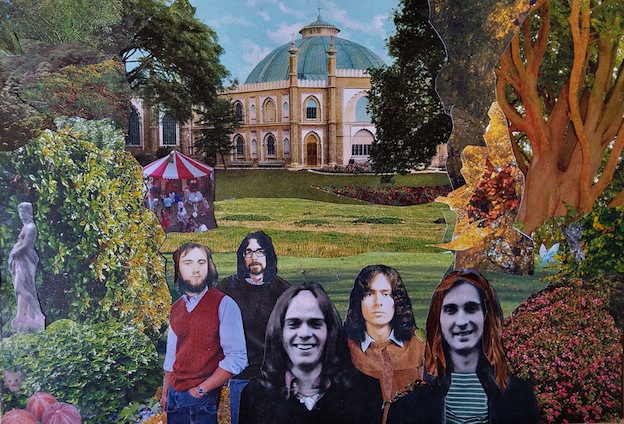

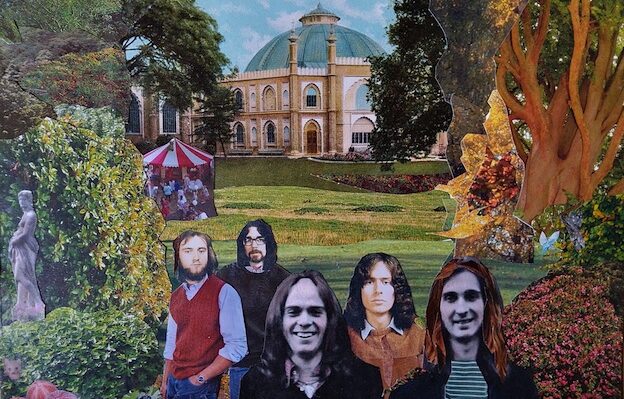

Back then, Genesis were a five-piece band fronted by Peter Gabriel, playing intense progressive rock songs with complex structures and difficult time signatures. I’m guessing that I heard a couple of their tracks on the radio. I must have enjoyed them, because I started buying their albums with the money I’d received from a part-time job in the school holidays. The first I had was Nursery Cryme, which I loved, and then there was Foxtrot, which was even better. I was excited to see what they’d do next. One day in September, shortly before the release of their album Selling England by the Pound, I noticed that Genesis were embarking on a British tour to promote it. These were the first dates I saw advertised:

Friday 5th October: Apollo Centre, Glasgow

Saturday 6th October: Opera House, Manchester

Sunday 7th October: New Theatre, Oxford

Thursday 11th October: Gaumont, Southampton

Friday 12th October: Winter Gardens, Bournemouth

Monday 15th October: Dome, Brighton

Tuesday 16th October: Colston Hall, Bristol

Thursday 18th October: De Montfort Hall, Leicester

Tuesday 19th October: Rainbow, London

Wednesday 20th October: Rainbow, London

Tuesday 23rd October: Empire Theatre, Liverpool

Friday 26th October: City Hall, Newcastle

Sunday 28th October: Hippodrome, Birmingham

The word “Brighton” leapt out at me. I lived with my parents in Crawley, Sussex, and we had often taken the train to Brighton for a day at the seaside. Brighton – London-by-the-Sea, Old Ocean’s Bauble, the Queen of Watering Holes – was a town of quaint and curious shops, where I had spent my pocket money on cheap conjuring tricks, and patches and brass buttons to sew on my favourite bomber jacket. It was an arty place with rough edges, where the theatrical legend Laurence Olivier still lived and where mods and rockers had notoriously fought on the beach in the 1960s. Back in September 1973, unbeknown to me, The Who were thinking about Brighton too, hard at work on their Quadrophenia album in the recording studio.

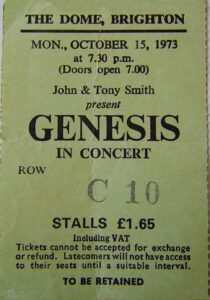

I resolved to lose my concert virginity, and discussed the Brighton Dome gig with a school friend who was similarly intrigued by Genesis. One of us applied to the Dome’s box office – we probably sent a postal order – and we received two tickets in the stalls, at £1.65 each.

A couple of weeks before the concert, the new Genesis record was released, and I bought a copy and immersed myself. It was wonderful, even better than I had expected. Selling England by the Pound is now considered by many fans to be the band’s finest album. Steve Hackett, their lead guitarist when they made it, has also said that it is his favourite Genesis long-player. For me, it’s an inspired distillation of the essence of the band at the time, which just happened to be a creative peak for one of Britain’s most original rock groups. SEBTP was the first Genesis album to reach the Top 10 in the UK and to chart in America. It was a clear progression from their previous albums – justifying the term “progressive” in one sense – and can be seen as a loose concept album about the nature of “Englishness”. The concept-album classification is reinforced by the record’s lyrical themes, its general bucolic atmosphere, and the fact that its closing track, ‘Aisle of Plenty’, harks back musically to the opener, ‘Dancing with the Moonlit Knight’.

October 15 was otherwise an ordinary school Monday. I was a fifth-former receiving a comprehensive education in English, mathematics, French, German, Latin, art and biology. Soon after returning home that day, I boarded a train with my friend. Inside my duffel bag was a biology exercise book, because I planned to do the evening’s homework on the way. Also in the bag was my Philips mono cassette recorder, loaded with a fresh Prinzsound C120 tape (one hour’s duration on each side), with which I would make an illegal recording of the evening’s concert. That way, we could enjoy the gig over and over again, albeit in a lo-fi way.

The autumnal smells of leaf mould and woodsmoke mingled with more exotic whiffs of cannabis, patchouli oil and Afghan coats

We arrived at the Dome and joined the queue outside. It was already clear in the gloom of the evening that we were two of the youngest people here. Most of the crowd looked like college students, office workers and seasoned gig-goers. Around 7pm the doors to the venue were ceremoniously unbolted by liveried officials, and hundreds of us filed in to the grand old building, which in the early 19th century had been the stables for dozens of horses owned by the Prince Regent, close to his seaside residence of Brighton Pavilion. The autumnal outdoor smells of leaf mould and woodsmoke were mingling now with more exotic Seventies whiffs of cannabis, patchouli oil and Afghan coats.

I was concerned that the security staff here would find my tape recorder and confiscate it, but I was lucky. Nobody checked the contents of my bag, despite the fact that there had recently been IRA bombings in England. After we found our seats, I discreetly attached the microphone to the back of the seat in front of me with a loop of Sellotape. I had to remove it when some latecomers joined our row and needed to squeeze past us to reach their seats, but I was able to reattach it.

Eventuall y a twentysomething man with the air of a trendy teacher bounded onto the stage and welcomed us. “During Genesis’ set, if you can keep well back from the stage,” he advised, “because there are going to be a few surprises.” This was greeted by a few excited cheers. “Just remain in your seats if you can.” He announced that the support act on the tour was an artist who “had done a lot of work with Roger Waters of the Floyd, and with Pete Townshend.” There were low noises of appreciation at those names, and the MC then asked us to “put your hands together for Ron Geesin”. Geesin turned out to be an apparently eccentric Scottish solo performer, at one point accompanying himself on a one-string banjo. I can hear an audience member on my tape conclude rather harshly: “He’s a nutter, obviously.” But Geesin’s CV is impressive: he has scored feature films, and he composed brass, choir and cello parts for the long title track on Pink Floyd’s Atom Heart Mother, among many other things. Years later, I was intrigued to discover that he had once lived in Crawley.

y a twentysomething man with the air of a trendy teacher bounded onto the stage and welcomed us. “During Genesis’ set, if you can keep well back from the stage,” he advised, “because there are going to be a few surprises.” This was greeted by a few excited cheers. “Just remain in your seats if you can.” He announced that the support act on the tour was an artist who “had done a lot of work with Roger Waters of the Floyd, and with Pete Townshend.” There were low noises of appreciation at those names, and the MC then asked us to “put your hands together for Ron Geesin”. Geesin turned out to be an apparently eccentric Scottish solo performer, at one point accompanying himself on a one-string banjo. I can hear an audience member on my tape conclude rather harshly: “He’s a nutter, obviously.” But Geesin’s CV is impressive: he has scored feature films, and he composed brass, choir and cello parts for the long title track on Pink Floyd’s Atom Heart Mother, among many other things. Years later, I was intrigued to discover that he had once lived in Crawley.

Genesis later appeared on a darkened stage as we heard keyboardist Tony Banks play the doomy Mellotron chords that begin ‘Watcher of the Skies’, from Foxtrot. Peter Gabriel sang as the sinister, all-seeing Watcher himself, dressed in black, wearing a head-piece featuring a pair of bat wings, his eyes ringed with white make-up that glowed in the ultraviolet rays from the stage lights. After the song reached its dramatic finale, he remained on stage and assembled his next outfit as we watched. “This is a little unfamiliar, perhaps,” he said (because it was new for this tour). “It’s a costume some may recognise… Here we have a little bit of red, white and blue,” he said, indicating the Union Jack emblazoned on his chest. “Then we add a little bit of feather – or tail feather, as it’s known in the business.” Donning a plumed leathery cap, he had become the legendary patriotic figure of Britannia – “The voice of Britain,” he explained. At other gigs he had expanded on this line, adding “before the Daily Express”, because “The voice of Britain” was how the populist old right-wing newspaper described itself on its masthead.

Now he burst into the acapella opening lines to ‘Dancing with the Moonlit Knight’. The band joined in slowly and subtly, then carried the song through its series of rousing passages, the wild sounds coming from Hackett’s Les Paul guitar belying his sober, bearded and bespectacled appearance. The song ended with a quiet pastoral section of tinkling 12-string guitar and decorative puffs of Gabriel’s flute – a sound painting of an idyllic English woodland, perhaps – for which the audience sat quietly and appreciatively.

There was something a little peculiar about Romeo. He used to grow little green fig leaves round about here…

What was striking, though I was new to live concerts, was that most of the band were sitting down. Of course, one usually expects the drummer to be sedentary, and often the keyboard player, but not the guitarist or bass player. It gave the ensemble the feel of a small orchestra, though Gabriel compensated for his bandmates’ stillness and earnestness with his costumes and theatrical hyperactivity. He prefaced the next song, also from SEBTP, with one of his trademark whimsical stories:

“Romeo, once upon a time, met a little girl called Juliet… There was something a little peculiar about Romeo. He used to grow little green fig leaves round about here [indicating his crotch]… And one day he decided to pick one of these little green fig leaves, and off it went. And he stuck it under his arm, which is where he kept all his precious things, for several weeks… He removed it, and it had changed to a deep maroon colour. He then ate the leaf and disposed of it. Meanwhile, this induced in him a high state of sexual excitement, and he met his little Juliet in the cinema. And this is how Romeo and Juliet… [rapidly, in a high-pitched voice] whup-whup-whup-whup-whup-whup… in the… er, cinema. The result of this labour was ‘The Cinema Show’.”

Gabriel’s pre-song stories began partly out of necessity. Tony Banks once recalled: “When Peter first went on stage, he didn’t really know what to do and he developed his persona. Some of it was by chance, but otherwise he had to tell his stories as we kept having equipment breakdowns and 12-string [guitar] tunings.”

The lyrics to ‘The Cinema Show’ were a collaboration between Banks and bassist/guitarist Mike Rutherford, and were inspired by the section in TS Eliot’s The Waste Land in which the seer and narrator Tiresias watches as a typist is seduced in her London flat by a “small house agent’s clerk”. But it was Gabriel who had suggested naming the characters in the song Romeo and Juliet. The song worked well live, with its narrative verses bursting into a sunny chorus-of-sorts full of profound imagery, and its closing instrumental passage in 7/8 time played by Rutherford, Banks and Collins and stuffed to bursting with melodic synthesiser phrases.

Other keyboardists might have used this section to play a long improvised solo, different every time, but this wasn’t Banks’s style, and not only did he construct his parts before playing on the record, but he reproduced them note-for-note on stage. He later explained: “I am not an improviser in a group situation. I can improvise and play away for hours at home. But when I am restricted to a riff or chord sequence I prefer to work out my playing in advance.”

A long, low Mellotron note suggested the approach of an electric lawnmower

‘The Cinema Show’ ended abruptly on stage, rather than seguing into ‘Aisle of Plenty’ as it does on the record. Gabriel made a point of commending “Michael, Tony and Phil” to the audience for their performance, which is interesting given that he had initially argued against that instrumental section being included on the album. Then he announced, “Now we venture to a more agricultural vein,” and a long, low Mellotron note suggested the approach of an electric lawnmower.

Wearing a peculiar hat, with a long blade of grass clenched in his teeth, Gabriel pushed an imaginary grass-cutting machine along the stage before announcing “It’s time for lunch,” and the band kicked in with ‘I Know What I Like (In Your Wardrobe)’. More psychedelic than prog, the song worked better as a piece crafted in the recording studio than it did on stage here, though members of the audience couldn’t resist singing along with the infectious chorus. ‘IKWIL’ has one of my favourite Genesis lines: “There’s a future for you in the fire-escape trade; come up to town.” It would be released as a single four months later, becoming the band’s first-ever Top 30 hit and receiving the honour of a routine by the house dancers on Top of the Pops, Pan’s People.

The lyric to The Battle of Epping Forest runs to about 800 words, making it a challenge to reproduce live

After the roar of the lawnmower faded, the band burst into ‘Firth of Fifth’, though it lacked Banks’ complex grand-piano intro, which he did play on electric piano at other venues on this tour. But the second highlight of Banks’ song is the mellifluous guitar solo from Hackett, which was spine-tingling on stage.

The oldest song tonight was ‘The Musical Box’, an old favourite from the 1971 Nursery Cryme album, and then Gabriel took a break as Phil Collins stepped up to the microphone to sing ‘More Fool Me’, the tune co-written by him and Rutherford on SEBTP. It wasn’t a first for Collins: he had sung ‘For Absent Friends’ on Nursery Cryme. But I never imagined, and nor did anyone else, that this very capable drummer had a future as a monstrously successful solo singer.

Next, a marching drumbeat took us to a leafy part of southwestern Essex. ‘The Battle of Epping Forest’, describing a violent confrontation between East End gangsters, works as a cautionary tale for lyricists. Gabriel’s rapid-fire lyric, full of characters and wordplay, runs to about 800 words, making it a challenge for any singer to reproduce live without a written aide-memoire. He managed it reasonably well, perhaps because he had recorded the vocals just two months before, but he did make several errors. He left out the lines “Yes, these Christian soldiers fight to protect the poor. East End heroes got to score in…” just before a chorus, replacing it with a previous line about a gangland boundary instead. He completely transposed two sections with the same tune, one beginning “Amidst the battle roar, accountants keep the score” and the other “Up, up above the crowd, inside their Silver Cloud”. He shuffled the line “She rang the bell and quick as hell” in the Reverend passage. And he missed out a couple of good lines in the final chorus, “We guard your souls for peanuts. And we guard your shops and houses for just a little more,” replacing them with the previously sung lines about the Civil War. To be fair, I only noticed the mistakes when I played the tape for the second or third time, and his blunders didn’t throw the band at any point in this fiendishly difficult song.

During the number, Gabriel took on the guise of the aforementioned Reverend, the posh vicar who goes over to the dark side; it was yet another character, yet another chance to dress up. At the time, there was an argument raging among music fans that Genesis were “too theatrical”: that all the Gabriel costumes and masks were a distraction that was overshadowing the music, which was of paramount importance. At least, that was the opinion of the musical puritans. But once I’d seen Genesis in concert, I disagreed. The Gabriel characters were there to illustrate the songs, just as children’s books have pictures to accompany the stories, and just as magazine articles have photographs. The Gabriel characters reinforced the band’s songs and gave them an extra dimension. When music videos became de rigueur a decade later, I hardly ever heard anyone say “Oh, the video’s overshadowing the music.” The visuals were an addition, not a subtraction.

‘The Battle of Epping Forest’ was the last SEBTP song Genesis would play that night, though the gig was far from finished. Gabriel’s next stage story was quite a long one, suggesting that there was a fair amount of tuning up to do, and perhaps that we were in for a correspondingly long piece of music.

So welcoming was the green grass that old Michael took off all his clothes, and began to rub his body on the fresh grass

“Old Michael,” he began, “walked past the pet shop, which was never closed, into the park, which was never open.” (On reflection, this didn’t make a lot of sense: if the park was always closed, how could he enter it? He had apparently garbled the story: when he told it at other gigs, the pet shop was never open and the park never closed.)

“And the park was very clean, green and smooth. So welcoming was the green grass that old Michael took off all his clothes, and began to rub his body on the fresh grass, accompanied by a bit of a tune. It went like this…” After a few seconds of comical wordless singing, Gabriel explained that beneath the ground, the earthworm population had become excited by the sounds from above, which they interpreted as rainfall. “For the worms, rain can mean only two things: mating, or bath time. They enjoyed both.” Within seconds, the green grass was covered with writhing brown worms. “Michael was also pleased, and began to whistle a little tune. It went like this…”

Accompanied by some basic kit percussion from Phil Collins, the “little tune” was recognisable as an uptempo mangling of the hymn ‘Jerusalem’. “For us,” said Gabriel, “it was Jerusalem boogie. But for the birds, it meant that supper was ready.” A roar went up from the crowd, because we were in for a treat. ‘Supper’s Ready’ was their epic from Foxtrot. This was their ‘Close to the Edge’, their ‘Echoes’, their 20-minute-plus meisterwerk. To this day, it is rated by many people as the greatest prog number ever written.

And towards the end of the “song” came a major surprise – and the main reason why we had been warned to keep away from the stage. As the band burst into the glorious final section, there was a dazzling flash of light – a magnesium flare, which I could feel the heat of – and when we had all come to our senses, we saw Peter Gabriel flying high above the stage. At least that’s how it appeared, though we knew he must have been suspended on an invisible wire. He continued to sing as he swung about, dressed in a natty silver suit. Imagine: this was my first-ever rock concert, and the lead singer was defying gravity at the end of it.

It was the end: many of us clapped and stamped and shouted “More!” for a good few minutes before, hands sore and voices hoarse, we realised there would be no encore that evening. “How could they have followed that?” I hear a voice say now, but personally I would have welcomed a rendition of ‘Can-Utility and the Coastliners’ or ‘Twilight Alehouse’ to round the night off. ♦

© 2023 Tony Barrell

Tony Barrell is a grown-up now. He is the author of many press articles and a series of acclaimed books on music, including Rock’n’Roll London and The Beatles on the Roof.

0 comments found

Comments for: GENESIS REVELATION