London’s Hyde Park was once famous for staging free rock concerts. And in 1969, the Rolling Stones made history here. Tony Barrell reports

JUNE 2020

There have been some unusual sights to see in Hyde Park over the years. Back in the 18th century, dukes and earls played cricket on this lush swathe of London greenery, and angry men fought duels here, pacing up and down and firing pistols to settle their scores. Later, Queen Victoria would enjoy riding through the park in a carriage with her husband, Prince Albert. But none of the Georgians or Victorians who romped in this park could possibly have imagined the scene here in the 1960s, when long-haired young men and women danced and chilled in the sunshine to the sound of electric guitars and drums.

The park’s first big rock concert took place on June 29, 1968, when the sun shone and young people flocked to an event billed as the Midsummer High Weekend. Pink Floyd, Tyrannosaurus Rex, Jethro Tull and Roy Harper all played in the Cockpit area of the park, near the recreational lake known as the Serpentine. The loud music was a balm and a distraction in troubled times: the Vietnam War was raging, Bobby Kennedy had been shot, students had rioted in Paris, and activists and desperadoes were hijacking planes and flying them to Cuba.

John Peel hired a boat and rowed on the Serpentine as he soaked up the sound of Pink Floyd

That Saturday, the disc jockey and writer John Peel was one of the thousands enjoying the space rock of Pink Floyd, whose songwriter Syd Barrett had been replaced in the lineup by guitarist David Gilmour. They released their second album, A Saucerful of Secrets, on the same day, and would play three pieces from it – the title track, plus ‘Let There Be More Light’ and ‘Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun’ – along with ‘Interstellar Overdrive’ from their previous album. Peel hired a boat and rowed on the Serpentine amid other waterborne hippies as he soaked up the sounds. He wrote that he had never heard “the Floyd” play better: “I don’t know whether the unique atmosphere or the closeness of the sky, the earth and the water drew out their best. There was no anger or violence in what they did and the sounds fell around our bodies with the touch of velvet and the taste of honey.”

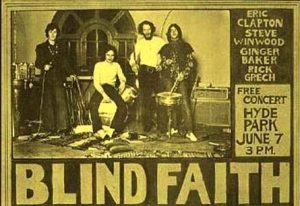

Other free Hyde Park gigs followed that year, featuring bands including Traffic, the Nice, Fleetwood Mac (before their 1970s reinvention), Family, Fairport Convention and the Move. And as the weather warmed up in 1969, the sound of music returned to the park. Artists including Lulu, Long John Baldry and Julie Driscoll entertained some thinnish crowds on Friday, June 6, but most rock fans were eagerly awaiting the Saturday, when a new “supergroup” was due to make its debut. This was Blind Faith, comprising Eric Clapton, Steve Winwood, Ginger Baker and Rick Grech. Clapton and Baker had been two-thirds of Cream, which had bid its farewells at the end of ’68. Winwood had recently sung and played keyboards and guitar in Traffic, and Grech had played bass in Family. The name of the new band was appropriate for the occasion, as their debut album (and final album, as it turned out) wouldn’t be released for a few months, so the Hyde Park throng of about 100,000 gathered on the strength of their individual pedigrees alone.

Expectations were too high, and the gig was a mild disappointment. The band appeared to lack confidence and precision, and Clapton did a lot of slouching against his stack of Marshall amplifiers. Winwood stuck to Hammond organ, but clearly pleased the crowd with his impassioned vocals – there was a reverential hush as he sang ‘Presence of the Lord’ – and Baker’s energetic, jazzy drumming drew cheers and whistles, especially on ‘Do What You Like’. Winwood later reflected: “Hyde Park was our first gig. Doing it in front of 100,000 people was not the best situation. Nerves were showing and it was very daunting. We couldn’t relax like you can on tour.”

“I was nervous at Hyde Park,” said Rick Grech. “I think everybody was. We knew the numbers, but not to the extent of not having to think about them. I’m sure the majority of the audience expected the band to sound like Cream, and that’s not the way it is. Cream was three virtuosos, all improvising. We’re not out to out-solo each other.”

Mick Jagger and Marianne Faithfull were in the audience that day. Asked for his opinion on Blind Faith, Jagger replied: “I thought they were very nice. I was right at the back of the stage and couldn’t see them. But I thought somehow they were very strained. I guess they’ll get more together. And Ginger was fantastic. He’s a beautiful drummer – the best drummer I have ever heard. I was a bit surprised Steve didn’t play any guitar, though. I wish he had stood up and played; I love to see Steve wiggle his bum a bit!”

The Stones were working at Olympic Sound Studios in Barnes when they received the news that Brian Jones was dead

Less than a month later, Jagger would be up on the stage here himself, playing one of the most iconic gigs in rock history. But the Rolling Stones had some difficult days to endure before they played the park. By the time of the Blind Faith gig, they had already found a guitarist to replace Brian Jones, the 27-year-old founder member who had given the band their name, but was now unreliable and often out of his mind on illicit substances. His recent drugs conviction also scuppered their plans to tour the USA, for which he had been denied an entry visa. At the end of May, Mick Taylor had joined them in the studio, playing on ‘Honky Tonk Women’, and had been accepted as the new Stone. On June 8, three members of the band – Jagger, Keith Richards and Charlie Watts – travelled to Brian Jones’ home in Sussex to fire him in person.

Early in the morning of July 3, two days before their scheduled concert in Hyde Park, the Stones were working at Olympic Sound Studio in Barnes, West London, when they received some devastating news. Brian had been pronounced dead after being found at the bottom of his swimming pool. A coroner later noted that his liver and heart were enlarged owing to drug and alcohol abuse, and concluded that this was “death by misadventure”. The Stones wondered whether they should pull out of the Hyde Park event in honour of Brian, but drummer Charlie Watts suggested that they play it as a tribute for him. Mick Taylor later said: “A lot of people expected us to cancel our free concert in Hyde Park, but that would have been wrong. Brian would have wanted us to do it. It was the best thing we could have done.”

They had chosen a favourable day for the concert. The week had been a warm one, and on this sunny Saturday afternoon the temperature reached a pleasant 22C. Around 5.15pm, after sets from support bands including King Crimson, Family and Alexis Korner’s New Church, the Rolling Stones took to the stage. “Okay, now listen, now will you just cool it, just for a minute,” urged Jagger, “because I really would like to say something for Brian.” There were at least 250,000 people in the park, the biggest audience the Stones had played to at that point, and many of them were refusing to cool it. “Are you going to be quiet or not?” he asked, and then consulted a book to read those famous lines from Adonaïs, written by Shelley in 1821, shortly after the death of John Keats at the age of 25. “Peace, peace! he is not dead, he doth not sleep. He hath awakened from the dream of life…”

Some observers claimed that Jagger was wearing a “dress” or even a “little girl’s white party frock”. In fact, he was wearing a costume inspired by the uniform of the Greek National Guard, a white tunic-and-trousers ensemble created by the British fashion designer Michael Fish. It came from his boutique, Mr Fish, which had opened in 1966 at 17 Clifford Street, off Savile Row. The shop sold the outfit at 85 guineas apiece to other customers too, including Sammy Davis Jr, who liked it so much that he bought it in three colours (black, brown and champagne).

Jagger probably had this image of these thousands of butterflies soaring majestically heavenward. But they’d been cooped up in those boxes for so long that most of them were half dead already

Andy Taylor, a teenage rock fan from the East End of London, was in Hyde Park to see the Stones. “There were so many people there, and unless you’d camped overnight you didn’t get anywhere near the stage. I was somewhere in the middle of the park, sitting between two trees, and I couldn’t see the stage. I heard Mick Jagger recite the poem, but I couldn’t see him.”

Several cardboard boxes were opened to release 3,500 white butterflies, many of which flew for a short while before landing and perishing. “Even as far back as I was, I had the odd one land on me,” recalled Andy Taylor. “Jagger probably had this image of these thousands of butterflies soaring majestically heavenward. Unfortunately, they’d been cooped up in those boxes for so long that when they chucked them into the crowd, most of them were half dead already.” The labelling on at least one of the boxes revealed that it had previously been used to carry packets of chicken-flavoured crisps.

The band opened with a cover version, ‘I’m Yours and I’m Hers’, a Johnny Winter number that was said to have been Brian Jones’ favourite song when he died. Several of the Stones’ originals followed, including ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’, ‘(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction’, ‘Street Fighting Man’ and their latest single, ‘Honky Tonk Women’. If they sounded a little ragged round the edges, they could be forgiven. They hadn’t played a concert in public for more than two years, they had just suffered a tragedy and they were inducting a new band member. They had rehearsed for the concert in the Beatles’ Apple studio at 3 Savile Row, but Jagger had been hampered by a bout of laryngitis. For people a long way from the stage, the music wasn’t even particularly loud, such was the vastness of the park in relation to the power of the PA system. Fortunately, the gig was filmed by Granada Television, and viewers were able to see and hear it properly two months later.

Many of the thousands sitting on the grass and climbing the trees were long-haired rock fans who could be loosely classified as hippies. Stomping around among them, hired as informal security for the day, were young men in biker gear who were thought to be Hells Angels, but were actually a group of East Londoners called the Forest Gate Greasers. “And I saw two skinheads with braces and boots,” said Andy Taylor, “but I didn’t know they were called skinheads until that day. They came through the crowd and stood there, blocking the view, and this girl sitting in front of me booted the back of this bloke’s Dr Martens and said, ‘Get out of the way!’ And I heard this northern bloke say, ‘Bloody skinheads!’ In the ’60s you sat down at concerts, unlike today.”

If you collected three bags of rubbish and brought them back, they gave you a free single, a copy of Honky Tonk Women

There were celebrities enjoying the gig as well, including Paul McCartney, Keith Moon, Eric Clapton, Ginger Baker, Germaine Greer, and Viv Stanshall from the Bonzo Dog Band. At least two of Jagger’s squeezes were present: Marianne Faithfull and Marsha Hunt. And wandering through the park were two young art students wearing smart suits and metallic bronze make-up. These were the artists Gilbert & George in their guise as living, singing sculptures, years before they became much more famous after winning the Turner Prize for art in 1986.

The Stones may have cultivated an image as bad boys for much of the 1960s, but they apparently wanted to make a good impression with Westminster City Council that day. “People were handing out empty rubbish bags,” said Andy Taylor, “and if you collected three bags of rubbish and brought them back, they gave you a free single, a copy of ‘Honky Tonk Women’. I collected three bags and got one. Considering it was 1969, it was quite an ecologically sound thing to do.”

On the other hand, the Stones had annoyed the British Butterfly Conservation Society, whose chairman dashed off a letter to The Times denouncing “the wanton releasing of butterflies in a park without food-plants in the centre of a large city”. Later it became clear that some of the insects had survived and flown out of the park: there was a minor plague of caterpillars in gardens and allotments in and around London.

The Rolling Stones eventually brought Saturday’s proceedings to a close with a hugely extended version of ‘Sympathy for the Devil’, during which they were joined on stage by African tribal drummers, emphasising the atavistic black roots of their music almost to the point of self-parody. Then one of the world’s most famous concerts – by no means perfect, but endlessly memorable and the subject of a billion conversations ever since – was over.

In 1985 a journalist asked Mick Jagger what the Stones’ happiest moment up to that point had been. “God!” he exclaimed. “The Rolling Stones do not tend to be associated with happy moments. It was like kicking people in the teeth all the time and just being happy that you survived. The Hyde Park concert was a wonderful moment, though.” What about the butterflies, asked the writer. “Yes, well,” said Jagger, “the event was tinged with all the poor butterflies, and poor Brian Jones. It was tinged with sadness, but it was still a wonderful moment.” ♦

© 2020 Tony Barrell

Tony Barrell is the author of several books on music, including Rock’n’Roll London and The Beatles on the Roof.

0 comments found

Comments for: HYDE TIMES