Britain has hundreds of thousands of pagans. Are they a force for good or ill? Tony Barrell meets some extraordinary men and women

THE SUNDAY TIMES, 2001

Concerned you may have pagans living in your neighbourhood? Well, around Christmastime, here’s one of the signs to look for: their homes are likely to be decked out with ilex and Viscum album. It’s the time of the winter solstice, you see, so they like to have a bit of holly and mistletoe around. There might be a yule log crackling in the cosy hearth. Oh, and they will be indulging in a shameless orgy of present-giving. Still concerned?

Now, let’s turn the wheel of the year back to mid-May, between the pagan festivals of Beltane and Midsummer. You see a poster advertising a Pagan Federation day out. It’s called the Leaping Hare event, and it features “music, real ale… socialising, ritual, food & silly games”. This turns out to be one of the hottest Saturdays of the year, and given that pagans love nature – sunlight, the open air and fresh greenery – Leaping Hare sounds like a heap of fun. It’s in Chelmsford, but even that doesn’t put you off, so you go along.

You descend a metal stair into a poky basement room at Essex County Hall. When your eyes have adjusted to the gloom, you see a few rows of chairs in front of a television set. There are sandwiches curling on side tables, and medallioned men carrying pints from the bar. There are women with long dyed hair wearing shawls, and the odd tiara. Rumour has it that the sun is still blazing outside. “This afternoon,” announces a blonde woman at the front of the class, “we’re going to indulge in the age-old pagan tradition of watching telly.”

Well, blessed be, as pagans say. During the talk on “magic in the movies” that follows, about 70 rather cramped men and women watch a long series of video clips. The speaker, Levannah Morgan, gives a lively critique of each film, discussing how pagan sorcery is represented in each case. The Wizard of Oz is apparently “based on strong kabbalistic principles” and has “the best portrayal of a witch on a broomstick ever”, while the television series The Craft has “all the form of witchcraft, without the content”. The theme is the portrayal of witches in mass entertainment. But this very event seems a sad reflection on pagans. What are they all cooped up here, worshipping the cathode ray tube, rather than hugging trees and romping in robes across Chelmsford Park?

Paganism is said to be Britain’s fastest-growing religion, though this is impossible to substantiate when so many pagans go about their business so shyly and secretively

Several weeks earlier, there had been an “open ritual” in London to celebrate the spring equinox. The venue was Red Lion Square in the City, which sounded provocative: thousands of freaky new-agers using their magic to storm the pinstriped bastion of British capitalism. But the word “open” referred only to the admission policy, and the event was enclosed in a darkened hall, at a safe remove from bowler-hats who might object to an overt reverence of the greenwood instead of the greenback.

Paganism is said to be Britain’s fastest-growing religion – though the claim remains impossible to substantiate when so many pagans go about their business so shyly and secretively. Estimates in the late 1990s put Britain’s pagan population between 100,000 and 120,000. Andy Norfolk, a spokesman for the Pagan Federation (PF), has since made his own calculations, and says the true figure would now be closer to 225,000. That’s not to say that there are a quarter of a million people all believing exactly the same thing: just as there are thousands of Christian denominations, “pagan” is a catch-all term for a rainbow of mystical persuasions – mainly druidry, witchcraft, shamanism and Norse mythology. There is also a statistically elusive number of solitary witches – often called “hedge witches” – who fall outside the main categories. “Pagans tend to be hideously individualistic,” says Norfolk, “and a lot of them don’t like joining things.”

A lot of them don’t want to be identified, either. At both Leaping Hare and the spring equinox ritual, photography was strictly prohibited. “It does seem a big issue for pagans, just how open they should be about the reality of their beliefs,” says Norfolk. “Unfortunately, many are still concerned that if their employers find out they are pagan, it could affect their career.” Indeed, one of the reasons the PF was set up, in 1971, was to counter prejudice. “A large number of cases that we deal with, sadly, involve the break-up of marriages or partnerships, where one partner is trying to use the other’s beliefs to deny them access to the children.”

In the imaginations of the public at large, pagans may be Marilyn Manson lookalikes who romp naked through the forests of Britain, enjoying mass orgies and roasting babies for Satan. The truth may disappoint you: not only do they have nothing to do with Satanism or sacrifice (Satan, they say, is part of the bipolar theology of Christianity), but most of them appear to be decent, law-abiding people with proper jobs, who just happen to enjoy the occasional peaceful little ritual. They celebrate the solstices, the equinoxes and other ancient festivals like Imbolc, Lammas and Samhain (their word for Hallowe’en). For some, it seems little more than a harmless hobby: as in the worlds of amateur dramatics and battle re-enacting, you get to make new friends and do some fun dressing-up.

These two Christians were sat opposite me, two stereotypical little old ladies, and they had such a go at me: ‘Jesus died for your sins,’ and this, that and the other

But pagans are in a trap, a vicious circle. While the secrecy surrounding their activities protects them from persecution, it also feeds the ignorance and mythology that can lead to persecution. The “burning times” of the 16th and 17th centuries may now be denounced as a historic aberration – with scholars still debating whether the number of “witches” roasted and garrotted and impaled and drowned across Europe ran into the hundreds of thousands or into the millions – but anti-pagan sympathies can still be aroused by something as trivial as reading the wrong paperback in public.

Recently, Heathwitch Running Wolf, a 22-year-old pagan whose real name is Heather, was travelling home after work by train from Manchester to Broadbottom, engrossed in a book about witchcraft. “These two Christians were sat opposite me,” she says, “two stereotypical little old ladies, and they had such a go at me – ‘Jesus died for your sins,’ and this, that and the other. They ended up snapping and shouting at me so much that other people in the carriage were like, ‘Why can’t you shut up? She wasn’t doing anything wrong.’” The old ladies had picked on the wrong person: Heathwitch is one of the founders of the support group Apris (Accepting Pagan Religions in Society), which, like the PF, tries to defend pagans and to correct misinformation.

But asking different pagans about their true beliefs will get you a bewildering variety of answers. Responses may begin: “This isn’t true of all pagans, but…” or “This is my personal opinion…” At times it is like interviewing politicians who are terrified of going off-message and losing the party whip.

Before the London spring equinox ritual, I asked 36-year-old David Rankine, who was to be officiating as high priest, what he believed. “First of all,” he began, “the word ‘believe’ comes into question here, because paganism tends to be very experiential as a spiritual path.” Do pagans believe in life after death? “It tends to be down to a personal perspective, but I think most pagans do.”

“I do,” says his girlfriend, the high priestess Sorita, 28, “I’m personally sure that I have lived before.”

If somebody wants to do a spell to attract love, then it’s negative if they try to get a particular person, because they’re imposing their will on that person

David and Sorita are practitioners and teachers of wicca, the witchy belief system that came into being in the mid-20th century and is the most popular of all the pagan “paths”. Wiccans do actually practise witchcraft – though it isn’t the “black magic” or voodoo that may come to mind. There is a commandment – the “wiccan rede” – that stipulates you must never cause harm to anyone or anything with your magic. On top of that is the “law of threefold return”, which states that if you put out negative vibes, they eventually rebound on you with thrice the power. Teachers of wicca continually advise against love magic, which is inevitably No 1 in the worldwide most-requested-spell charts.

“If somebody wants to do a spell to attract love,” says David, “then it’s negative if they try to get a particular person, because they’re imposing their will on that person. However, if they decide to do something to make themselves feel better, then that’s positive, and they’re more likely to attract love into their lives. You are increasing the amount of energy going out into the universe, you’re shifting probabilities in your favour, which is one of the ways I describe magic. The most common thing that I would do a spell for is healing.”

You also have to be careful what you wish for, says Sorita. “One lady recounted to me recently how her friend had cast a spell to find the perfect lover. She wanted him to be blond, 6ft 2in, with blue eyes and a sense of humour. Very shortly afterwards, Mr Perfect arrives – and he’s a comedian, and he drove her barmy because he didn’t stop telling jokes.”

More than 100 oddballs joined hands and cantered around at a London spring-equinox ritual

The materials needed to cast wiccan spells vary from the mundane to the arcane: candles, crystals, coins, gold, frankincense, myrrh, scissors, paper, stones, water, apples, salt, cauldrons, pentagrams, ritual knives, wandsm and – yes – besoms, or witches’ brooms. The invocations often come with a few sheaves of corn, too. A rite for “safe astral travel” posted recently on a British website begins: “Oh Mighty Power that rules this place! Grant me safe passage through time and space! Protect me from forces of evil and hate. Guide me now safely to my true fate…”

As more than 100 oddballs joined hands and cantered around widdershins (anticlockwise) at the London spring-equinox ritual, they chanted a little rhyme to rid Britain of foot-and-mouth disease. It went: “Hare spirit swift as lightning, These afflictions need a-frightening, Lady Bright and Lord of Might, Send them from us, give them flight.”

“Lady Bright and Lord of Might”? People who routinely use “pagan” as a synonym for “godless” are in for a shock here, because many wiccans and other pagans believe in a spectacular line-up of deities – particularly goddesses, as the divine forces in nature are largely perceived as feminine and maternal. A big favourite of pagans is the great “mother goddess”, her male consort being “the horned god” – a wild bigwig of the forest who has been mistaken for Satan over the centuries.

Which deities do David and Sorita worship? “Ah, well,” says David, “we’re back to the use-of-words thing here. We celebrate our deities rather than worship them. The relationship is not about being on bent knee; we have fun with our deities.”

Do pagans have favourites? “Yes,” says David, “some have particular goddesses or gods that they’re a priestess or priest of. There are an awful number of priests and priestesses of Isis out there, for example.”

“In my house,” says Sorita, “I’ve got shrines to Isis, Aphrodite and various other deities. But a shrine can just be a little table or shelf.”

“Isis was celebrated in ancient Egypt,” explains David, “and she was known as the goddess of 10,000 names. She represents the benevolent, compassionate, wise, feminine, creative force. You know, a lot of the titles attributed to the Virgin Mary were originally Isis titles. There’s that whole image of Mary in white and blue – and those are colours Isis used to wear.”

If you talk to most pagans for long enough, you can bet your crystal ball you will arrive at this theme – how later religions appropriated many of the old pagan trappings. “Christmas is a classic example,” says Sorita. “Christians put up Christmas trees, but that’s not a Christian tradition, and nor is the gift-giving. And at Easter you give children eggs and bunnies. This comes from the goddess Eostre, who was walking in a field when she found a bird that was badly injured. The only way she could heal it was by changing it into a hare. The problem was, the hare was still laying eggs. Which is where the whole bunny-and-egg thing comes from.”

If druidry doesn’t ring your bell, there are always the Norse gods like Odin and Thor, familiar to many of us who grew up with the superheroes of Marvel Comics

Druids may celebrate the same festivals as wiccans, and wear similar robes, but they are fundamentally different, according to Emma Restall Orr, a 36-year-old female priest who co-runs the British Druid Order. “Druidry tends to find its essence – its power, if you like – by invoking spirits of place: the spirits of the land and the spirits of ancestry, primarily,” she explains. “If there are deities, they come second. Also, for me, druidry is not a magical tradition, which wicca is. Druidry is based on inspiration and creativity, as opposed to magic.” There are fewer sacred tools involved, too: “Another major difference is that we don’t use a lot of cutlery.”

If druidry doesn’t ring your bell, there are always the Norse gods – characters like Odin and Thor, the thunder god, already familiar to many of us who grew up with the superheroes of Marvel Comics. The former PF president Pete Jennings, 48, decided in his thirties that the “northern tradition” (also known as heathenism, or Asatru) was the path for him. “Part of it is to do with where I live,” he says. “A lot of the place names in East Anglia are either old Norse or Saxon. Also, the northern tradition is very in-your-face, it’s not all fluffy and tree-huggy.” The world we live in, apparently, is just the central one of nine worlds, all connected to a “world tree” called Yggdrasil. Our world is Midgard, the world of gods is called Asgard, and there is a world of giants called Jötunheim. Using meditation, Pete has actually travelled between the worlds. “Once, I went to the edge of Jötunheim, which is reckoned to be one of the most dangerous places to go. But the giants aren’t like your Victorian fairy-book jobbies: they’re like large natural forces. The giantess that I saw there was in the form of a giant waterfall.” The northern path is one of the hardest to follow, says Pete. “You really have to find your own way. Nothing is handed to you on a plate.”

It is true of pagans generally that they don’t hawk their beliefs around: you won’t find them proselytising in the street, or hammering on the door, selling you magazines. “We don’t go out and recruit people,” says Sorita. “What happens is that you find yourself drawn to a certain path – and if you’re drawn to it, you will eventually find people.”

“When the time is right,” proclaims David, “the teacher will appear.”

Children and teenagers will surf pagan websites after reading Harry Potter books, or watching television shows like Charmed and Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Sorita and David receive countless entertainment-inspired emails asking for magical advice – and they exercise caution if the senders are under 18. “I get people of 14 or 15 contacting me, who want to come along to a ritual or to our wicca training course,” says Sorita. “And I can’t say yes, because if I do, it gets out and people say, ‘Ooh, it’s a cult and you’re pulling young children into it, you wicked witch.’”

“It’s a double standard,” says David. “If a child becomes interested in paganism,they cannot get involved until they’re 18. However. it’s fine for them to go to Sunday school.” Before this becomes an anti-Christian tirade, he adds a typically conciliatory pagan footnote: “And that’s fair enough, because the Church is the established religion.”

Nevertheless, adults often say that it was youthful experiences that led them up the pagan path. Sorita’s introduction to wicca came in her teens, via an electrician who came to her mother’s house in South Africa. David says it began for him when he started precociously reading about world mythologies at the age of four.

I saw a 7ft-tall Native American man standing at the bottom of my bed. At first it was frightening, and I hid under the bedclothes. But he kept reappearing

The shamanic drummer Barbara Meiklejohn-Free, now 45, was a three-year-old girl living in Scotland when strange things started happening to her. “I saw a 7ft-tall Native American man standing at the bottom of my bed,” she recalls. “At first it was frightening, and I hid under the bedclothes. But he kept reappearing. He wouldn’t say anything – he was just a wonderful presence. I’d say to my parents, ‘Why is this happening?’, but they didn’t know. Many years later I went to America, and I saw these cards in a shop, and on one of them was the person I’d seen. His name was Touch the Clouds, and he worked with Crazy Horse.” Since then, Barbara has followed the Native American shamanic path, has learnt to heal people with drums, and has been given the “medicine name” of Morning Star Hawk Woman.

People come to paganism in less spectacular ways, too, through an interest in tarot cards, crystals, astrology, numerology, out-of-body experiences, or all manner of new-age subjects. “A lot of people come into wicca via the environmental movement,” says David, “because wicca is so eco-friendly. Or from feminism, because wicca is so feminine.”

Equally, one might happen across a gig by a band like Inkubus Sukkubus, a Gloucester-based four-piece who have been belting out full-on goth rock for 13 years. Their eight albums include no-holds-barred songs with titles like ‘Pagan Born’, ‘Vampyre Erotica’, ‘Whore of Heaven’, and ‘We Belong with the Dead’. “I would hate to think that we’re out there converting,” says their 35-year-old female singer, Candia McKormack, “like a pagan version of Cliff Richard, with followers saying, ‘Oh, thank you, you’re doing so much for the pagan cause.’ But sometimes people have said they’ve been along to listen to the band and it’s been a way into paganism for them.” Doesn’t their demonic name reinforce all the wrong ideas about pagans? “It’s supposed to be a bit tongue-in-cheek,” says Candia’s husband, 40-year-old guitarist and composer Tony McKormack. “We used to be called Belas Knap, which is a local burial mound, but it rhymes with ‘crap’.”

Candia and Tony are solitary witches who shun the wiccan movement, seeing it as too structured and doctrinal. They also don’t take the idea of goddesses and gods too seriously. “I think that’s just a way of interpreting certain forces,” says Tony. “The actual energy is nebulous, and viewing it as deities is one way of understanding it. Because of the goddess thing, a lot of people say that all pagans have done is ‘stuck tits on Jesus’. That’s probably a valid criticism, to be honest.”

At one Inkubus Sukkubus gig at London’s Marquee, the band shared the stage with a 9ft-tall home-made John Barleycorn, or wicker man. “He ended up dancing in the audience,” says Candia, “and some people took him off clubbing at the end of the gig.” Another concert was dignified by a phallus-shaped maypole. “There was a smoke machine in the base,” she says, “and the idea was that the smoke would go shooting out the top, a bit suggestively. But it started seeping out the bottom and leaking all over the stage.”

If I had a prejudice before I researched this feature, it was that I would get to see pagans running around naked in the woods

Even a common-or-garden maypole, the kind with ribbons on, is a fertility symbol in a religion that emphasises sexuality rather than covering it up. Besoms, too, are supposed to represent a union of male (the stick) and female (the brush). If I had a prejudice before I researched this feature, it was that I would get to see a bunch of pagans running around naked in the woods, maybe even practising free love. “You’re not going to be that lucky,” Sorita laughs. They call it “sky-clad” rather than “naked”, David explains. “And the sky-clad thing usually only happens among people who have been initiated into a coven,” he says, “among people who have strong bonds of trust. You would have to go through the whole training process and have been initiated as a witch. Some covens do, some don’t, and some just do it when the weather’s nice.”

Of course, it’s not always pleasant or amusing when rituals take on a sexual quality. Three years ago, a British writer (who prefers not to give her name) became involved in a pagan group in north London. “The goddess-centred nature of paganism appealed to me,” she says. “Also, the nature aspect was very attractive to me, and it was plugging into a lot of my other interests, like meditation.” She was going to meetings for about a year, and got on well with the group leaders – a married couple in their seventies – until she went to one particular ritual. “It was at the couple’s house, with a very small party of people. Suddenly the woman got up behind this screen, dressed as a goddess, and was doing various incantations, and her husband came in as the horned god, knelt down at her feet and was praising her. And then she took her top off. I actually felt it was a bit pervy, and I felt abused for having to sit there and watch it.”

Here is proof, then, that people can work “magic” with good intentions and still cause harm, effectively breaking the wiccan rede. Maybe she would have been better off watching telly in a basement in Chelmsford.

**************************************************

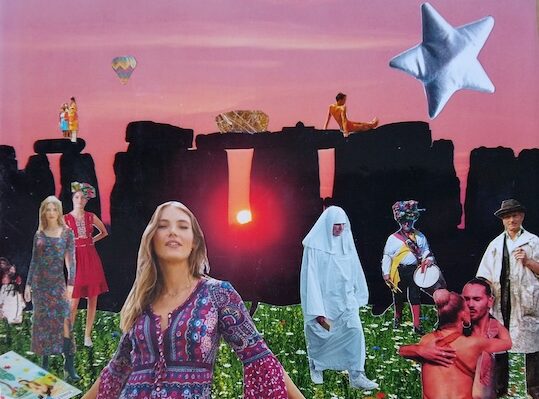

Like most other religions, paganism is backward-looking, even positively old-fashioned. Its adherents wear robes, ivy crowns, drink mead, and attend traditional “handfastings” instead of modern weddings. On June 21, 2001, thousands of them descended on their supernatural habitat, Stonehenge – at a reassuring distance from the industrialised Christian world – to see the sun rise on the summer solstice.

But nine days earlier, there should have been a much more lavish national celebration, a real occasion for looking back with profound gratitude. Tuesday, June 12, 2001, was the 50th anniversary of the repeal of the 1735 Witchcraft Act: for exactly a half-century, magicians had been allowed to go about their business with the full blessing of the law. The streets and fields and forests of Britain should have been filled with pointy hats and pentagrams, invocations and chants and hurrahs.

Here and there, people had small private gatherings. Other, lone pagans meditated by their shrines, arranged crystals and other esoterica, or updated their websites. Some just watched telly. Britain still isn’t ready for a Pagan Pride march. ♦

© 2014 Tony Barrell

Tony Barrell is an author, journalist, editor, lexicographer and raconteur who lives in London. Here’s one of his BOOKS.

0 comments found

Comments for: TO BE A PAGAN