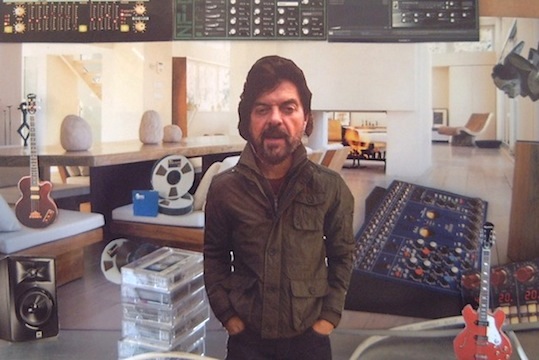

Alan Parsons – the studio wizard who worked with the Beatles and engineered Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon – rewinds his unique career in music. Interview by Tony Barrell

THE SUNDAY TIMES, JULY 2007

I started life in a musical family, one of the few gentile families in Golders Green in London. My mother sang traditional Scottish folk songs with a clarsach, a kind of Celtic harp, and my father played the flute and the piano. Also, he was always tinkering and inventing things, and I think that rubbed off on me. As well as studying music, I became interested in electronics when I was 10 or 11, and I remember building a three-transistor radio set in my bedroom. The entire object of the exercise was to pick up Radio Luxembourg and listen to it in bed at night. Although I didn’t know it at the time, I think I already had the qualifications for a career in audio.

Another gadget I made, when I was boarding at Westminster school, was an alarm system to alert us that the housemaster was making his rounds. There was a pressure-sensitive switch in the floor, which triggered a light in the dormitory. Occasionally it didn’t work and we got caught red-handed, talking, eating, drinking and pillow-fighting after lights out.

At the age of 19 I became a trainee tape operator at Abbey Road

I left school at 16 having been considered an academic failure: a vocational guidance counsellor suggested leaving was the best thing, because I wouldn’t do well at A-levels. And I went straight to work for EMI in Hayes, Middlesex. At first I was in a television-camera research lab, but after about a year I graduated to a department making prerecorded reel-to-reel tapes – this was just before cassettes appeared. But I really wanted to work at Abbey Road Studios, and the clincher was when I first heard the Beatles’ Sgt Pepper album, which just sounded incredible. About six months later, at the age of 19, I became a trainee tape operator at Abbey Road. Being a “tape op” basically involved pressing the recording button, finding the right place on the tape for overdubs, logging tapes, moving mikes around, and making endless cups of tea and coffee late at night – that was part of the job description.

Then, of course, the opportunity of a lifetime came up: to work with the Beatles, on their Let It Be album (as it was later called), which was being recorded at their own studios in Savile Row. That resulted in me being around for their last live performance, the famous rooftop concert. Glyn Johns, the Beatles’ recording engineer at the time, was down in the basement for that session and I was up on the roof, in communication with him. It was a very windy morning that day, Thursday, January 30, 1969, and there was a lot of wind noise getting into the microphones, so before the gig Glyn asked me to go out and buy some ladies’ stockings to drape over the mikes. Off I went to Marks & Sparks on Oxford Street, and they said: “Yes, sir, what size?” I said: “It really doesn’t matter.” So they thought I was either going to rob a bank, I think, or I was a cross-dresser. I was behind a camera to stage right for most of the concert – if I had a chance to relive that day, I’d make sure that I was photographed.

My first session as an engineer, in the hot seat, was with the Hollies in 1970

I wanted to learn as much as I could as quickly as possible, so I could progress to becoming a recording engineer, or balance engineer, as EMI called it. The balance engineer is the person who basically sits at the console, presses buttons and moves the faders up and down; he’s essentially responsible for the sound. And finally it happened. My first session as an engineer, in the hot seat, was with the Hollies in 1970, recording the single ‘Gasoline Alley Bred’. It went well, but I ended up cringing every time I heard it, because I was so green and I could’ve made it better if I’d had the experience.

When I engineered The Dark Side of the Moon for Pink Floyd, it changed everything. It was a very challenging project: they treated the studio as an instrument, and used the facilities at Abbey Road to the nth degree. There’s no doubt that influenced what I wanted to achieve in my own work.

I progressed to producer soon after that, and almost immediately, as luck would have it, had two consecutive No 1 singles, with the band Pilot and Steve Harley and Cockney Rebel. And then, in 1975, the manager and songwriter Eric Woolfson came into the picture and said: “You’re doing well as a producer, but I have this vision of you making a concept album.” We came up with the idea of doing something based on the work of Edgar Allan Poe, and I thought I’d just get a producer’s credit. The last thing I expected was that the UK record label, Charisma, would promote me as the artist. It became Tales of Mystery and Imagination by the Alan Parsons Project. And that was literally how people had referred to the project in the corridors of the label, early on: “How’s the Alan Parsons project coming on?”

Essentially I felt I was still doing the same job as before, producing various musicians – people like Arthur Brown and John Miles – but this time I was involved in the compositional process and everything was compiled together and put out under my name. It was a very strange transition from being out of the limelight, behind the glass in the studio, to suddenly having a record out with my name on it, doing radio promotion and signing autographs.

The French refer to artists as chanteurs, so the French press would say: “Alan Parsons est le chanteur de Tales of Mystery and Imagination…” And in the late ’70s the US music-industry magazine Cashbox voted me 13th best male vocalist – and I barely sang anything on the albums apart from a few oooohs and aaaahs. I was right below Neil Diamond and just above Cat Stevens. ♦

© 2020 Tony Barrell

Tony Barrell’s acclaimed and bestselling book The Beatles on the Roof is available now from good bookshops in the UK, North America, Australia and Japan.

0 comments found

Comments for: PARSONS KNOWS