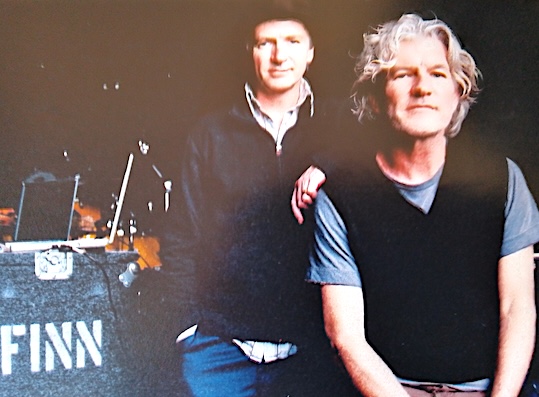

The brothers Neil and Tim Finn discuss their New Zealand upbringing, Split Enz and Crowded House, and their musical differences. Interviews by Tony Barrell

THE SUNDAY TIMES, MARCH 2005 (expanded version)

NEIL FINN:

When we were growing up in Te Awamutu, on the North Island of New Zealand, Tim used to tell me far-fetched stories full of wondrous goings-on. Once, he told me a Martian had taken over his body: “My name is Soupy the Martian and I’ve taken over your brother’s body. Your brother is now on Mars.” I didn’t believe him at first, but I decided it must be true because he went on and on about it.

Mum was a good harmoniser, and she steered us into finding harmonies while we were doing the dishes. If Mum and Dad had people over, Tim and I would be hauled out to sing in front of them. We’d sing ‘Jamaica Farewell’, as sung by Harry Belafonte, and ‘Terry’, a tragic motorbike song. It was an odd song for little kids to be singing. I was attracted to the lower harmonies; I think I was, at least subconsciously, responding to the fact that I liked the sound of John Lennon’s voice under Paul McCartney’s. There was a nasal quality, which I think I also had.

Tim went into the counterculture enthusiastically: everything from demonstrating against the Vietnam War to taking psychedelic substances

When I was young I idolised Tim, who’s six years older than me – it seemed like he was doing everything that was exciting about being an adult. He went to boarding school – Sacred Heart College in Auckland – and that seemed a very romantic notion: boys in a dormitory having pillow fights and getting caned. He was caned many times; he had the record in the third form for the cane. Then he went to university, which was even more glamorous from afar, because he grew his hair and went into the counterculture enthusiastically: everything from demonstrating against the Vietnam War to taking psychedelic substances. When I went to Sacred Heart he bought me The Little Red Schoolbook, a subversive manual for teenagers that gave you advice about everything from drugs to contraception. It was very controversial and considered obscene. It said masturbation was okay, and various other things that were not supposed to be okay. So I was ending up in meaningless, pseudo-political confrontations with the Catholic brothers, and the book was confiscated. Which was just as well, because I think Tim was trying to encourage me to scrawl obscenities on the chapel wall! I think he was just into the idea of anarchy, and because I was buying into it big-time, he saw me as a protégé in protest at that point.

Tim formed Split Enz, which in any circumstances, anywhere in the world, would be an extraordinarily unusual band. In New Zealand it was particularly so. Then they relocated to England, and that seemed almost unimaginable – that your brother might be in a band that’s getting some notice in England. Tim was actually called Brian up to that point – when Split Enz started, for some reason most of them changed to their second names. When they asked me to join, when I was 18, it was phenomenal. It was a bit of a shock to step into that role: I had only played acoustic guitar, not electric guitar. But they knew I had some ability and that I would adapt. All the characters in the band were fascinating, and I was very excited to be amongst them. As the youngest, I had to go down and get the sandwiches every day, and I accepted that willingly.

Tim has always had a more ethereal bent. I’ve had a family since my early twenties, and that made me quite pragmatic. Tim was a single man for a long time, and while we were getting up at night and dealing with nappies, he was exploring his inner self, getting into Buddhism and meditation. Then he had some troubled relationships. There was a big change in our relationship when he broke up with his first wife; he had a bad time for a good six months and went plummeting into a bit of a funk. Instead of being the younger brother looking to him for role-model guidance, suddenly I saw him very vulnerable, and I had to try to help him get through it.

We have an unspoken agreement not to put each other through too much torment

It can be difficult working with Tim, because some of the things between us that come out in a musical context are deep, old things – little sensitivities that rise to the surface. We have an unspoken agreement not to put each other through too much torment. Maybe that’s not a good thing, because ultimately we might not confront certain things and they build up to resentments. We tend to save our fracas for a rainy day.

When we were making the album Everyone Is Here together [released in 2005], I started working on it at home, working long hours, and Tim’s concentration started to drift off. That was the darkest hour. We were asking: “Is there any reason why, just because we’re brothers, we should even work together?” I come to a record in a more detailed, nuts-and-bolts way, while Tim’s more into the performance: getting it down and getting out of there, pretty much. That frustrates me at times. I think: “Don’t you want to make it better? You just want to finish it.” Whereas he sometimes thinks I’m circling it too much and not committing. But part of the reason we have worked well together is because I need someone to pull me up and say: “Look!”

Yeah, he annoys me at times – he has a different way of looking at things, and sometimes it doesn’t make any sense to me – but ultimately, you know, it’s me and Tim against the world.

TIM FINN:

Neil was the perfect little brother in a way, because he would fit in with my fantasies and enjoy it. I used to read all those English comics, so I was able to project myself onto a cobbled street, dribbling with a soccer ball. I’d put Neil in goal and slam balls at him for hours on end; he didn’t seem to mind. Our Uncle George used to call him Nugget, because he was such a little guy, with freckles. He’s actually grown up to be perfectly average size-wise, but as a kid he looked nuggety and small.

All the family would go to the beach in the summer, and uncles and aunties and family friends would sit around and sing. It was a very Irish thing – Mum was born in Ireland and Finn’s an Irish name, so there must be Irish blood on Dad’s side too. There’d be all these sentimental songs like ‘When Irish Eyes Are Smiling’, and people would get drunk and be crying and feeling ridiculously Irish. Uncle George would sing ‘Shake Hands with a Millionaire’; a woman called Peggy Dawson would sing ‘Stormy Weather’ in this bluesy, gin-soaked voice, and Neil and I would be dragged out to sing some Fifties song. Often I’d sing the lead line and Neil sang a harmony underneath. He became very good at lower harmonies, and there’s something about that blood harmony that connects us in quite a deep way. I do consider it a fortunate thing that we had that together, because otherwise what would we have had to do with each other? Probably hardly anything. It was unlikely that a 10-year-old would play with a four-year-old. The singing was really our point of connection.

I was a hero figure to Neil for a while. It was a bit of a family joke that he idolised me. There’s a song on the album Everyone Is Here called ‘Disembodied Voices’, which is about how we used to talk at night with the lights off. And I think the real magic stuff must have been when I left Te Awamutu and brought back these exotic tales from my boarding-school life.

I formed Split Enz in 1972 with a guy called Phil Judd, and when Phil left five years later we needed a guitarist. Neil was 18 and he’d never played electric guitar, but we all knew he was musical: he’d actually supported Split Enz. He’d walked out on stage, as bold as you like, in front of 2,000 people at the age of 15 or 16 and sung his own songs.

I sat Neil down and said he should form his own band. So he did: he formed Crowded House

After I left Split Enz, Neil, out of guilt and loyalty, carried it on for a while. But he needed at that stage to find out who he was, because he had joined my band and was still living in my world, with my friends and the people I’d met. I remember sitting him down and saying: “I think you should form your own band.” So he did: he formed Crowded House. It wasn’t like he needed me to tell him that, but it probably gave him a kick-start.

Neil and I didn’t write together until we wrote some songs for Woodface [the 1991 Crowded House album] and I joined the band. When we wrote the song ‘Weather with You’, it was a perfect division of labour. I had the opening two chords on the guitar, Em7 to A9, and the line “Walking round the room singing ‘Stormy Weather’,” and Neil came back with “At 57 Mount Pleasant Street”. Actually, one of our two sisters lived at Mount Pleasant Road, and not at number 57 – so it was just a phrase that sang well. We took it from there, and completed the verse and the bridge (“Things ain’t cookin’ in my kitchen…”). Then a day or two later I realised this part I had, “Everywhere you go, you always take the weather with you,” would fit perfectly, would hammer it home.

Neil and I challenge each other and provoke and stimulate each other in a way that’s hard to explain. Making Everyone Is Here, there were frustrations with some of the songs. He finds it hard to cut off all possibilities. He’ll be like, “What if…” and he’ll keep chasing something, right up to the mastering stage. That’s a kind of perfectionism, but it’s also a kind of inability to make a decision. But because of that, you can get some really great music – but it can also drive you crazy.

We’re not good at fighting. It gets intense really quickly, then we both have to back off for a few days, or a few weeks. We sometimes play tennis, and that gets a bit fraught; every point is a blood point. So whilst we can work really well together songwriting, and we’ve learnt to be kind to each other and developed quite an honourable relationship, on the tennis court it becomes much more primal.

But Mum was never happier that when Neil and I were working together. She died four years ago, and in a sense we did Everyone Is Here for her. She used to play piano herself – everything in the same kind of swing time – and she was our first great audience. Here eyes would be shining. You couldn’t play long enough for her – she loved everything we did.♦

© 2024 Tony Barrell

This is an expanded version of the Finn interviews that were published in the ‘Relative Values’ slot in The Sunday Times Magazine during its golden age in 2005.

Tony Barrell has also been published by HarperCollins, Omnibus Press, ACC Art Books, and many others.

0 comments found

Comments for: THE MIGHTY FINNS