Tony Barrell explains why he wrote his new book about drummers – and discusses the hard work that went into it

APRIL 2015

During the radio interviews I’ve given to promote my new book, Born to Drum, one question has popped up over and over again. I think it confirms Barrell’s Law of Questions, which states that “The more unanswerable the question, the more it will be asked.” The question is this: who is my favourite drummer?

The first time I was asked that question, I made a “hmmm” noise and patiently explained that I don’t have one favourite drummer. By the third or fourth time, I’d become more playful. “It depends what day of the week it is,” I replied, generating a brief silence that radio people know as “dead air”. I explained that earlier that day, which was a Tuesday, I’d been listening to Keith Moon, but tomorrow I might be enjoying some Omar Hakim, and Thursday might be devoted to Clem Burke. It was essentially the same answer: I don’t have a single favourite drummer. If I did, I might have written a book about him or her, as opposed to a book about dozens of different drummers.

When I was about 14, I used my bed as a substitute drum kit

The second most asked question has been: why did you write a book about drumming? That’s a much better question, and it’s answerable. But if you ask many authors of drumming books that question, they’re able to give you a short answer. It’s because they play the drums. In my case it’s more complicated, because I’m not a drummer.

When I was about 14, I thought I was going to be a drummer, because I enjoyed using my bed as a substitute drum kit. I’d beat a pair of home-made sticks on the bed in time to the chart hits on the radio, attempting drum rolls and fills to make my playing sound interesting and clever. A couple of years later, I tried playing a real drum kit at a friend’s house, but I was deeply disheartened by my performance. I found it impossible to co-ordinate my hands and my feet so I could play the drums and cymbals while operating the pedals for the bass drum and hi-hat at the same time. I had a few more attempts but I eventually gave up, deciding that the drums were not for me. I took up the guitar instead.

I had to conduct the interview from the foot of Ginger Baker’s hotel bed, repeating several of my questions in a loud voice

But I still loved listening to drummers. In fact, I noticed that I enjoyed listening to drummers even more than before, because I had an increased respect for them. Having tried and failed to do what they did, I could suddenly see how skilful they were. I couldn’t get enough of great players like Phil Collins, Carl Palmer, Billy Cobham, and Paul Thompson of Roxy Music.

Decades later, a few other significant things happened. Firstly, I became a journalist, and started writing long magazine articles about musicians. In 2011 I interviewed Ginger Baker, which was a memorable experience. Ginger had recently turned 70. His back was giving him some trouble, so he had to lie down for much of the interview. Another problem was that he was very deaf. But despite the fact that I had to conduct the interview from the foot of his hotel bed, repeating several of my questions in a loud voice, it all went surprisingly well. We covered a lot of subject matter, from Cream to heroin, and from polo horses to the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins. I remember thinking: “I wonder if other drummers are this interesting…”

I didn’t act on that thought at the time, but shortly afterwards I had an email conversation with an old friend, who suggested out of the blue that I write a book about drummers. And the more I thought about it, the more appealing that idea became. (It’s a continual frustration to me that the best ideas seem to come from other people. “Why didn’t I think of that?” I ask myself repeatedly, as I bang my head rhythmically on the desk.)

So that’s the why question answered. But the question that so far nobody has asked me, and the one that I find most interesting of all, is: how? How did I write this book? That’s actually what I asked myself when I realised I’d finished it – written around 93,000 words, in a decent order. How the heck did I do that? I’d never written anything that long before, so it was a big surprise.

When I started Born to Drum, I knew it would involve a lot of research. But I love research, so that’s what I did. I spent long afternoons in the British Library, and huge stretches of time at home on the internet, learning about my subject. I got through dozens of books, some of them with the most tenuous connections to drumming. I travelled up a few blind alleys. While I was absorbing a stack of jazz biographies, collecting titbits of information about great players like Buddy Rich and Gene Krupa, I reached a decision. This would essentially be a book about rock and pop drummers, because if I broadened its scope to include jazz players, and maybe even orchestral drummers, the size of the project might be too daunting. Did I really want to spend several years writing a book that might run to 1,500 pages or more?

I started sending interview requests to famous drummers I admired, typing with my fingers tightly crossed

Meanwhile, I knew that I couldn’t linger among the dusty tomes. I needed to talk to actual drummers – quite a lot of drummers – to collect first-hand opinions and stories and ideas that would bring the book to life. I started sending interview requests to famous drummers I admired, typing with my fingers tightly crossed. The rejections followed: this drummer was up to his ears in the studio; that drummer wasn’t interested. The rejections were to be expected: I was trying to persuade busy musicians to put aside valuable time for a prospective publication – a book that was little more than a pipe dream at this stage, and might not be published for a few years.

There were many days when I wondered if I was wasting my time, but as I persisted, encouraging replies began to ping into my inbox. Early successes included face-to-face interviews with Nicko McBrain of Iron Maiden, and Nick Mason of Pink Floyd, and I started to feel I was getting somewhere.

I’m not exaggerating when I say that every single interview taught me something new about drummers. Ideas were raised that I hadn’t considered before, which often pointed me in fruitful new directions of research. Meanwhile, more of my interview requests were paying off. Some of the drummers I interviewed put me in touch with other drummers they knew. On a couple of occasions, drummers who had initially refused interviews (or whose management had refused interviews) suddenly agreed to talk. One day in 2013, as I received a “yes” from Phil Collins and another famous drummer just as I’d finished an interview with Queen’s Roger Taylor, I became aware that my project had acquired a new momentum. Apparently, it was being discussed here and there in drummers’ circles, and more of them were believing in this nonexistent thing that I was slowly bringing to life. And it wasn’t long before I called a halt to the interviews: after talking to my 38th drummer, I felt that I had more material than I needed.

The book seemed to develop a life of its own; it was an engine, driving me, rather than the other way round

Suddenly, I received an offer from HarperCollins for Born to Drum. Up till then, I’d been motoring steadily along on the project, enjoying the ride but never entirely sure if I wasn’t wasting months of my life. Now I shifted into top gear, setting my own strict deadlines for each chapter to ensure that I finished the first draft of my book on time. In a couple of cases, I had to give myself just two weeks to write a chapter of 7,000 to 10,000 words, and I worked long hours to do it – and to do it well. It was at this point that the book seemed to develop a life of its own; it was an engine, driving me, rather than the other way round. It had its own powerful internal logic and its own specific demands, which I was obliged to serve. The writing actually became more pleasurable and fluid then, because many of the decisions had already been made, I could see exactly where I was going, and I was gathering exactly the right information to get there.

That was very unlike the early stages of writing, when I hadn’t interviewed many drummers and I felt I was stumbling along slowly, groping to find my way in the dark. Several months later, the whole acceleration of the writing process, when everything seemed to come together at once (and I sometimes felt that “the book was writing me”) was a wonderful surprise; a delicious feeling I’d never experienced before. The strange thing is, I don’t have a distinct memory of writing some of those chapters – as if my brain temporarily evicted my memory-making faculties to make way for other, more urgently required skills. Sometimes I feel as if there was a mystical element in there as well: that I was being propelled by benign unseen forces of some kind.

I really hope I’m lucky enough to experience that miracle again at some point in my life. And I hope you enjoy the book. ♦

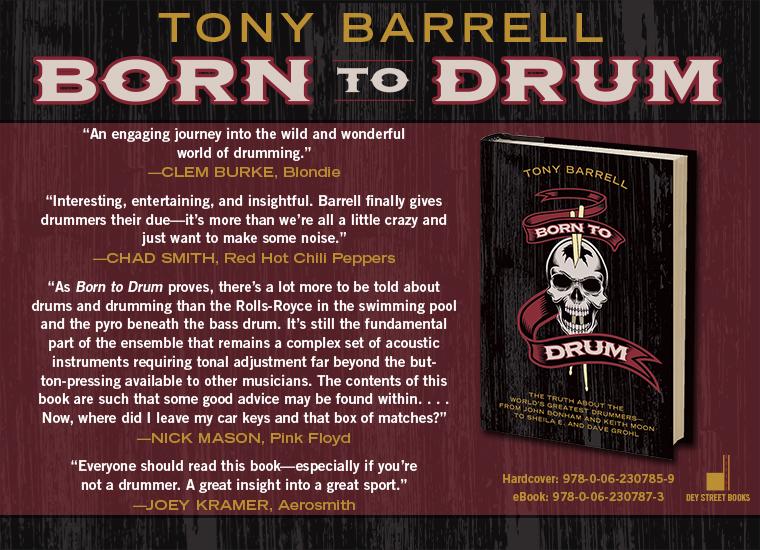

Born to Drum is available from many bookshops across the world.

© 2015 Tony Barrell

Very interesting to hear how it all came together. I really enjoyed the book. Your research is outstanding.

Great to hear how the writing process happened. Good job.

Fascinating stuff. I really enjoyed reading the book, and it’s very interesting to hear how it was written. More authors should do this.