He’s famous for instrumental epics such as Tubular Bells. So why is Mike Oldfield messing around with computer games? Tony Barrell reports

THE SUNDAY TIMES, 2002

Slow down. Chill out. Stop leaping around, raiding tombs and shooting people. There’s a new computer game to play, in which you get to have a nice time in an idyllic landscape and nobody gets hurt. It’s epic in scale and ambition, weirdly beautiful, rich in melody and texture, and has been painstakingly put together by a multi-talented composer called Mike Oldfield.

Tubular Bells topped the LP charts and turned Oldfield into a pop icon and guitar hero

Ring any bells? Thirty years ago, the same man started recording an album that moved the rock goalposts and launched the career of one of Britain’s toothiest multimillionaires. Despite being songless, almost drumless, and consisting of just two very long pieces of music, Tubular Bells topped the LP charts and turned Oldfield into a pop icon and guitar hero, and Richard Branson’s Virgin Records into a fabulously fertile business. Since those days, 40m Mike Oldfield albums have been bought around the world.

Back in 1972, he was a timid, bearded, long-haired 19-year-old laying down endless overdubs on primitive equipment in an Oxfordshire studio.The metamorphosis has been staggering. Now, as he demonstrates his sophisticated PC game in the studio of his Victorian farmhouse in Buckinghamshire, he looks just like a bright yellow butterfly, flapping and swooping over deserts, forests, mountains and seas. Don’t worry: this is just the virtual lepidopteran body the star has adopted in the game today, and the real Mike Oldfield is sitting next to me, clutching a computer mouse and following the butterfly’s flight on his jumbo-sized PC monitor.

As his butterfly soars, the 49-year-old composer explains what’s happening in the game – which can sometimes sound like nerdy gibberish to the uninitiated. “Oops, I’ve just gone through the boomerangs. Now the butterfly’s throwing boomerangs.” These are not weapons, however. “You can throw them around and have fun, but you mustn’t hit anybody.” Yes, there are other creatures in this world, and the game’s peace-and-love morality means you mustn’t harm them. Right now, there’s another pretty butterfly sharing Oldfield’s adventures; this turns out to be his computer-boffin assistant Nick Catcheside, who is operating a PC in another room and communicating with his boss by phone. The butterflies are just two of a range of usable screen bodies, or “avatars”, and Oldfield suddenly fancies a change. “I’m going to swap my butterfly for an emperor moth,” he says. But he’s lost sight of Nick. “Are you still a butterfly?” asks Oldfield down the phone. “Can you see me? I’m an emperor moth. I’ll meet you by the entrance to the tunnel, okay?”

Once people have his software, he says, a whole crowd of them can “meet” in this wonderful land by going onto the internet and talking into mobile phones. “You can spend the whole afternoon just wandering around. It would take days to explore every possibility in the game – and that’s if you know what you’re doing.” Along the way there are pleasant tasks to accomplish and – a particularly Hobbitty feature, this – a set of golden rings to collect. Achievements are rewarded by virtual transportation to extra-beautiful places and blasts of super-nice Mike Oldfield music. Doing good deeds is also good for the environment: it causes plants to start growing in the desert. But if you break the law – steal someone’s property, say – you get chased by a frightening black spaceship. And if you get too close to a shark, a viper or a scorpion, you can set off a volcano. Is it a bit like chaos theory then? “I suppose so,”, says Oldfield.

In the gaming industry the mentality is very basic, and it’s about violence

So there they both are, the moth and the butterfly, hovering by a small opening in a rock face. “If we take this short cut,” Oldfield explains to me, “we’ll pop out at the bottom of the sea with a whole load of dolphins.” Off he goes, a big blue moth exploring a world of his own creation. “Oh, this is fabulous! You see, I’m still discovering…. I’ve never done this. I’ve been here before, but not with this avatar. There we go!” Sure enough, we’re in the ocean and smiling dolphins are leaping all around us, accompanied by simulated splashes.

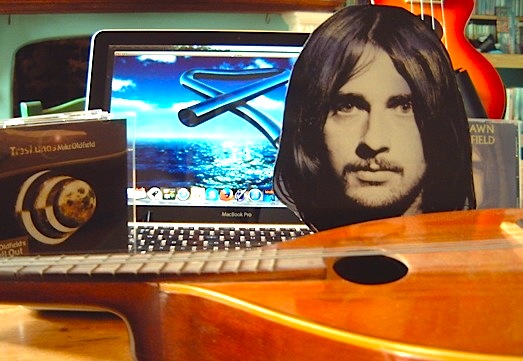

He calls the system MusicVR, or Music Virtual Reality, and the game, which may be the first “episode” of a series, is Tres Lunas (Spanish for Three Moons – a title inspired by one of his favourite restaurants in Ibiza). It has been more than two years in the making, and he has sunk “about £500,000 to £600,000” of his estimated £6m fortune in it. But history is repeating itself, because he’s had as much of a rough ride selling it to games companies as he did when he was trying to flog Tubular Bells to the big record labels. “I’ve had the games companies down,” he says. “They said, ‘It’s very nice, but nobody’s interested in that kind of thing.’ But a very young child would love it: it’s like going out in the garden and exploring. In the gaming industry the mentality is very basic, and it’s about violence. When I showed Activision this thing, they saw the dolphins and said, ‘How do you kill them?’” Only Warner Music in Spain, where he has a huge fan base, showed genuine enthusiasm, and is releasing Tres Lunas as a double CD. Buyers will receive nearly an hour of new Oldfield music – the Balearic-inspired “chillout” material you hear when you play the game – plus the game itself, the full version of which is activated by paying an extra £11.75.

Like a little tyke with a new Xbox, Oldfield can’t seem to keep his hands off the controls. “Shall we go on a space journey?” he suggests, and in seconds we’re approaching a Jupiter-class planet and triggering another harmonious sound file. “I’ve tried to put in everything I’ve ever wanted to do in my life – swimming with dolphins, travelling into outer space… playing football with upright pianos…” Before he can explain the keyboard-kicking, he spots a cosmic emergency: in the midst of space is a world with a foreign body circling it.”That comet is threatening that red planet. It’s getting quite close, so it’s a good idea to destroy it. It’s all right to destroy threatening things.”

He starts hurling projectiles at the comet: three strikes and it’s out. This gives us enough brownie points to take us to Good World, “just a beautiful place to hang out”, a utopia of pussycats and rainbows and heavenly shimmering. There’s a little pink Fender stratocaster guitar to play, just like the real one sitting nearby, amid all the other electrics and acoustics and basses and mandolins. Incidentally, when we want to leave Good World – even Oldfield can overdose on unalloyed niceness – we have to look for a little tubular bell, twisted into that pretzel shape we know from all those album covers. When we get closer to the bell, it turns magically into an evanescent flying horse.

Michael Gordon Oldfield was the boy who continually retreated into his own world, playing guitar in his bedroom, to escape from domestic turmoil

Psychoanalysts would have a whole month of field days, wouldn’t they? After all, Michael Gordon Oldfield was the boy who continually retreated into his own world, playing guitar in his bedroom, to escape from domestic turmoil. He was born in Reading, and his father, Raymond, was a pillar of the community, a hard-working GP. But Mike’s Irish mother, Maureen, was a depressive alcoholic who was repeatedly institutionalised. “I was only happy when I was playing guitar,” he recalls. “Music was my salvation.” He was playing at the local youth club by the age of 10, and formed a folk duo with his sister Sally, before joining the singer Kevin Ayers as a teenage bassist in his band, the Whole World.

In 1971 he was booked to play session bass for another band at Virgin’s new Manor studio in Oxfordshire, which is where one of Richard Branson’s colleagues overheard him tinkering with an early version of Tubular Bells. No deals were struck, however, and Oldfield “spent a long time hawking it round the other record companies and being thrown out the door”. He vividly remembers the moment, about a year later, when Virgin called him back. “I was thinking of going to live in Russia, as I’d heard you could be employed by the state as a musician there, and I was trying to find the number of the Russian embassy in the Yellow Pages when suddenly the phone was ringing. It was Simon Draper of Virgin, asking me to come and have dinner with them on a barge in Little Venice.”

Released in May 1973, Oldfield’s epic was lauded by pundits such as the DJ John Peel, who saw it as “a new recording of such strength, energy and beauty that it represents the first breakthrough into history that any musician regarded primarily as a rock musician has made”. The plaudits translated into cash, too. As Branson recalls in his autobiography, “We became rich beyond our dreams as the sales of Tubular Bells shot through silver, gold, platinum and then up over a million copies.”

I used to have these terrible panic attacks. The only thing that made me feel secure was alcohol

The trouble was, Oldfield was not in anything like the right mental condition to appreciate his overnight fame. It was time for another retreat. As Branson puts it tersely in his book, Oldfield “went to live in a remote part of Wales with a girlfriend, and refused to talk to anyone else except me….For the next ten years, Mike Oldfield lived as a recluse and did no promotion for any of his albums.”

“I felt like the black sheep of the human race,” Oldfield explains now. “For about 10 years, life for me was nightmarish. I used to have these terrible panic attacks. I didn’t know what was going to happen – if I was going to die, explode, go to hell… The only thing that made me feel secure was alcohol. So I’d be drinking half a bottle of brandy at lunchtime, till I got to the point of nearly having an ulcer and I had to stop. And I had all this insecurity because of taking too much acid, and because of my mother and her sickness. The only place I felt safe was on top of a Welsh mountain, with sheep everywhere. But I got over it.” He laughs – he can make light of it now – but it was a traumatic time, exacerbated by the death of his mother at the height of his fame.

It seems clear now why his work has defied classification from the beginning: people who don’t “fit in” create art that doesn’t fit in either. “Being creative is a wonderful thing,” he says, “but it is very stressful, and more often than not you’re terribly insecure inside; that’s why you create something, so that you’ve made something you feel safe in – almost like a different reality.”

I was back at the moment of my birth. I could feel the rawness of my skin touching the air, and I felt wet

In 1978 he discovered the root of his panic attacks at a trendy psychotherapeutic course called Exegesis, an offshoot of Erhard Seminar Training (EST), which taught him “that you create your own reality, and you can change your reality”. One particular exercise took him back 25 years: “They told me to make a sound. It started off as a whimper and ended up as a scream. The scream went on, and I was hyperventilating and all my muscles went stiff and I was sweating. Suddenly a whole bunch of people jumped on top of me with masses of soft cushions and pushed very hard, so I felt this tremendous comfort and security returning. The people gradually came off, until I was back at the moment of my birth. I could feel the rawness of my skin touching the air, and I felt wet. Obviously the memory of the birth is still in there somewhere, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the majority of people who have suffered panic attacks, all they’re reliving is birth traumas – the newborn baby is just scared. And when I found out, I thought, ‘Is that all I was scared of?’ As a result, I wasn’t panicky any more; I did all the things that I didn’t dare do before, like do interviews and learn to fly, because I could never go in an aeroplane before.”

Without Mike Oldfield, Richard Branson might have gone straight into condoms

But he wasn’t 100% cured, and still needs regular maintenance. “I’ve done a hell of a lot of psychotherapy over the years. It’s only one hour every two weeks now.” After his rebirth he continued releasing albums, having a hit single, Moonlight Shadow, but always failing to match the success of his debut. He had a string of love affairs, fathering five children – three with a publicist called Sally and two with a Norwegian singer called Anita. Meanwhile his relationship with Virgin deteriorated to the point that he put a crude Morse-code message to Branson on his 1990 album, Amarok – “F*** off RB.” What was that about? “I’d been contracted to Virgin for over 17 years, and ever since punk rock came along they couldn’t give a damn about me. I was paid a miserable royalty and they wouldn’t let me go. They were hanging onto me in case I made another Tubular Bells.” Virgin wouldn’t have existed without you, would it? “Urmmmmmmmm… not Virgin Records. But I’m sure Richard would have succeeded with something.” He might have gone straight into condoms. “Possibly!” he guffaws, as he hand-rolls himself a cigarette.

Rather pointedly, Oldfield went on to release Tubular Bells II after leaving Virgin and signing to Warner in 1992. Soon afterwards he was reborn again – this time as a bleached-blond Ibiza party animal. That was apparently The Sunday Times‘ fault. “I wanted to build a house and I was looking for a piece of land, somewhere warm by the sea. I was reading The Sunday Times, I think, and saw an advert for some land for sale in Ibiza.” It took two years to build and £2m – though he says the Ibiza experience nearly cost him his life too. He drank prodigious quantities of wine and acquired an ecstasy habit – “Ecstasy was a sort of normal after-dinner thing before you go to the clubs there.” Not only was he concerned for his health, but he found the resort cold and lonely in winter, and missed England.

His love life resembled his best music: romantic interludes broken by sudden changes of mood and loud rocky bits

He put the house on the market, but had no takers. “I was worried it was going to get like Ursula Andress’s house down on the coast, which has fallen into ruin.” Eventually he accepted an offer, for “a bit more than half” the original cost, from one Noel Gallagher. But Ibiza had inspired a danced-up version of his signature work, Tubular Bells III, and introduced him to the new love of his life, a pretty twenty-something French brunette called Fanny.

His love life thus far had resembled his best music: romantic, tranquil interludes broken by sudden changes of mood, emotional crescendos and loud rocky bits. This pattern seemed to be continuing: before I met Oldfield, the last thing I had read in the press about him and Fanny was a shock-horror piece in the Mirror last November, beginning “Mike Oldfield’s vengeful former lover is trying to sell sex videos of him dressed as a woman after walking out.” Was that true? “Yes,” he says. So he did dress as a woman? “Something I picked up in Ibiza,” he laughs. What was he wearing in the video? “That’s private.”

Who is he living with now? “Oh, we’re back together again, me and Fanny. We sorted that out.” He doesn’t want to say much more, except that Fanny works on his web pages, they’re very happy together, and will probably be married by the time this feature is published. Love conquers all.

“I still get insecure. I still get depressed sometimes,” he admits, as one of his four horses whinnies in the old field outside, “but it’s nothing like it used to be. I think getting a little bit older has helped.” Does he ride his horses? “No, I used to, but I had a terrible throwing-off one day, and I didn’t want to end up like Christopher Reeve.”

If Tres Lunas is a hit, he says, he will work on a sequel. But his next project is the realisation of a 30-year dream.”I’m going to re-record the original Tubular Bells,” he announces. Why? “Because it was done in such a rush – I barely had time to tune a guitar properly. There are fluffed notes everywhere.” In 1972, as a musical nonentity working on a pet project that nobody guessed would be massive, he had to snatch spare studio time whenever he could. “I can spend more time on it now, and do it so beautifully.” His music has more of a groove now, he says; a graceful flow that is lacking on much of that first record. “It’s the difference between watching an insect walking along the ground and watching a beautiful horse.”

There’s just one problem: he can’t find the original tubular bells he played on the album. They were hired for about £20, and he remembers wrecking one of the bells after hitting it with a heavy duty hammer instead of the traditional, more genteel mallet. “Then they got lost. Various people say they’ve got them, but they’re not the right ones. I’d know.”

Something tells me Mike Oldfield will always be searching for something. ♦

© 2014 Tony Barrell

Tony Barrell’s acclaimed new book, Beatlemania, is available across the world.

0 comments found

Comments for: VIRTUOSO REALITY